1918 – 1983

Richard Moketarinja showed the visual and cultural attributes of his country by experimenting in his compositional approaches. This sometimes involved exploring traditional aerial and European pictorial perspectives. The artist employed parallels in all compositions. Most have dots for infill or decoration and some paintings include zig zags.

Richard’s work in the Army labour unit during World War Two was his opportunity to express his pride and ambition in decorating souvenir mulga wood artefacts for receptive United States and Australian servicemen – in his spare time. He maximised the opportunity to earn the money, which was sent home to his wife, Gloria.

Richard started seriously to paint in watercolour in 1947 after Edwin Pareroultja’s first and successful exhibition in Melbourne in November 1946. Richard continued until around at least 1975. Rex Battarbee stated that he encouraged, rather than taught him.

In turning to the European convention of pictorial expression, he explored the difference between Arrernte aerial and European upright profile visual perspective. He manipulated compositionally to increase the effect of topographical characteristics. He portrayed the appearance of his country joyously and expressed its cultural attributes in pokerwork-drawn traditional symbols on the frame surrounding a painting. By the 1960s he presented a fantastic living country with trees as euphemisms for people, elders and perhaps ancestors. Richard’s landscapes appeared totemic and often animate. He was a founder and master of the Hermannsburg School.

Richard did not try to be prolific with high sales, but he had a long and steady career. Considered by the Mission to be a valuable station worker, Richard was not encouraged by the Mission to paint. He was fully engaged in each painting viewed in this research.

Richard was born in 1918 in Alice Springs. He attended the Mission school at Hermannsburg and worked on the Mission station. He was more distantly related to the rest of the founding group. Richard was Western Arrernte, Subsection Peltharre. He married a Loritja woman, Gloria (nee Emitja), and as at 1955 they had four sons and one daughter. He died near Hermannsburg in 1983.

Gloria (Nabitji) (c1922-82) was the daughter of Anthapa and Sandra (nee Pannka) Emitja and was thus a full sister of prominent artist Claude Pannka. Gloria was of the Loritja people and lived at Tempe Downs south of Hermannsburg. Personal information about Richard and Gloria originates from Rex Battarbee and the 1955 Northern Territory Register of Wards.

Many of Richard’s paintings were created in Palm Valley and some in the Glen Helen Valley and Gorge area.

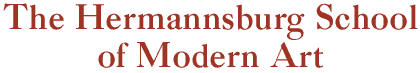

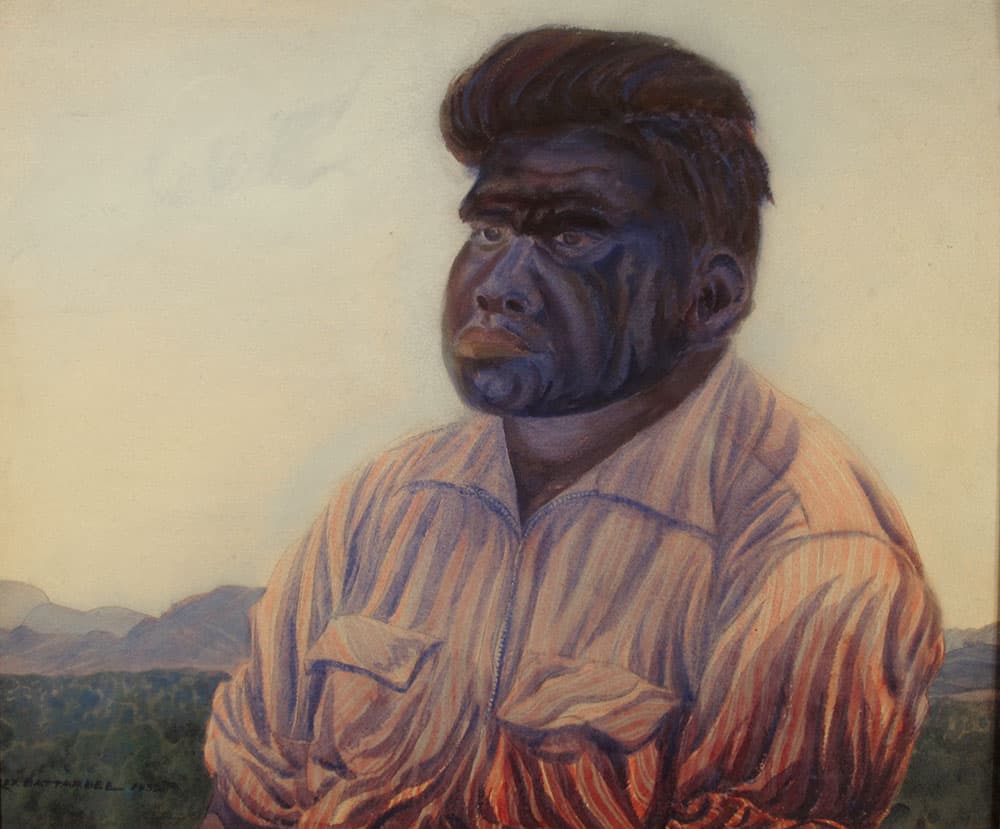

Rex Battarbee did a moving portrait of Richard in 1952, which paid homage to Richard’s system of painting and use of parallels as Rex employed his version of the prominent parallels as employed by Richard.

Portrait of Richard Moketarinja

Rex Battarbee

• • •

1952

Watercolour on paper

51 x 62 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

This describes Richard Moketarinja at 34 years of age in 1952. The painting has a flat pale cobalt blue sky and flat cobalt blue distant hill. The range of hills in front is described in ultramarine. Richard’s face is very dark and is painted in Richard’s frequently used colours of ultramarine and magenta. His shirt is elaborately striped in magenta and ultramarine straight and curved parallels and parallels are used on his head, and his dark ultramarine hair has dark magenta stripes. Richard’s lips are dark magenta.

Rex states that in 1940 (before the influx of US military servicemen) he became interested in Richard as an artist with outstanding drawing ability.

On a painting trip (by camel) Richard accompanied Rex (probably helping with the camels): ‘I used with Richard my method of encouragement without teaching. On this trip he painted some good watercolours which showed a lot of original primitive quality.’

During another camel trip with Rex and Albert in September 1941. Rex commented that… Richard came back this morning with the boys again; he did some painting today and quite a good Illumba [allumba] this afternoon… Richard was afraid Albert would laugh at his poor effort, but Albert said he would not. Rex commented on Richard’s ‘best effort of trip so far as he likes colour and seems to put it in the modern state’. Colour and design seems to be his big points ‘but he does not stick to nature the way Albert and I do’.

Richard found his own way with some guidance from Rex. Richard painted occasionally in 1941 but did not start to paint seriously until 1947. The author’s twenty-one paintings by Richard were made between 1947/48 and the 1970s and many of the dates are estimated by the author. His wife Gloria completed only a few paintings in the early 1950s.

Richard retained a more traditional ‘look’ in his painting than most of the other artists. He was the only artist known by the author to present a painting for sale with the wood frame decorated by traditional and cross cultural symbols in black pokerwork, apparently drawn by him. The painting and its frame comprised a unique concept of the watercolour portrayal of a particular part of a location, surrounded by a frame, which both set off the picture and also depicted various attributes of the area.

All of Richard’s paintings employed parallels as part of his system and most have dots for infill and decoration. He balanced the blandness of sky often with areas, which were not in-filled in the main part of the same painting, such as white tree trunks. A few paintings display his love of parallels prominently. Parallels are a characteristic of traditional Arrernte decoration on implements such as boomerangs and show considerable cultural pride. Also, many of his paintings employ zigzag marks in addition to parallels to invigorate his designs.

Spencer and Gillen, 1927, Fig 232 [1] has a photograph of ceremonial men ready for a rain dance or corroboree with the central man wearing a tall headdress with a prominent zigzag motif.

Significantly, Richard Moketarinja possibly preceded Edwin Pareroultja in breaking away from the style of Albert Namatjira in 1941 or 1942. Richard appears to have been the likely author of Mt Hermannsburg c 1940 illustrated as Figure 4.24 in Heritage of Namatjira. Figure 4.24 is stated to be by Otto Pareroultja, although it is unsigned and bears no characteristics of Otto’s approach when he started to paint many years later. This painting is in Flinders University Art Museum and was examined by the author.

In 1948 the urge to paint came uppermost and he spent the whole of 1948 in painting. In Battarbee’s opinion, of the Hermannsburg artists Richard improved the most during 1948. Writing in 1949, Rex also considered that ‘because of his originality and force of character he is not likely to be influenced by other artists.’

The earliest painting identified as by Richard Moketarinja is James Range, 1947 (watercolour on paper; 21 x 37.5 cm (irreg.); Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory NAM-0163). This interpretation concerns the interior of a gorge. Like the earlier painting described above, this employs yellow topped cliffs with dot/blob marks to suggest trees.

The next known painting by Richard is in the author’s collection.

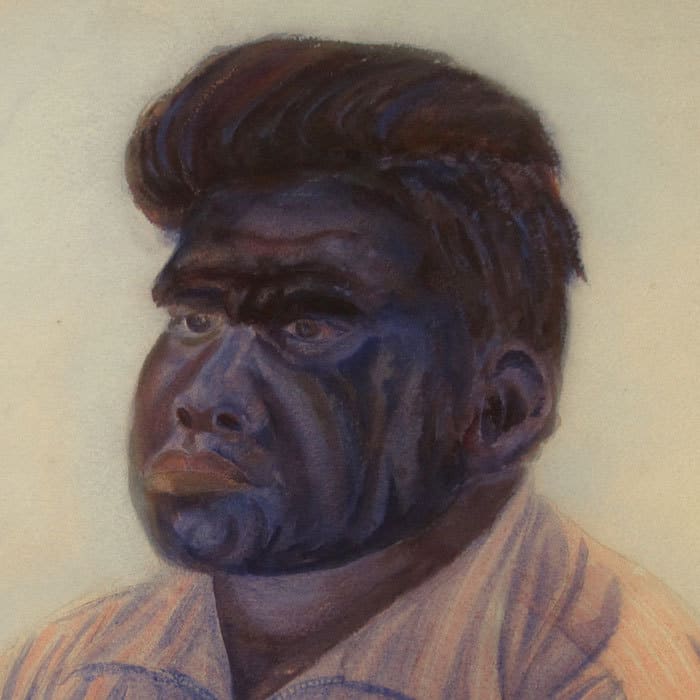

The Gap

Richard Moketarinja

• • •

est. 1947

Watercolour on paper.

24.5 x 36 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-RMo-03

The composition suggests that the viewer is floating through this gorge, with the viewpoint high above the ground. The viewer may feel included in the intimate space in this fine painting. On one hand, the reds in the painting become less intense with distance, while on the other hand, the yellow and green intensify from the mid ground towards the distance. The shadows are darker in the distance than in the nearer ground. Distance is suggested through recession in the pale ultramarine sky and convergence of the sides of the gorge.

There is much pale and intense lemon yellow. Dots and blob marks, parallels and geometrics are employed. Zigzags are used on the profile of the red rocky side, at left. Zigzags are modified at the right small outcrop. Pale 3-4 mm wide curved lateral parallels on hill bases on right side. Red foreground rocks each side sharpen the image as do the thin black trunks on small foreground trees.

Two Gums

Richard Moketarinja

• • •

est. late 1947 or 1948

Watercolour on paper

28.5 x 38.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-RMo-15

This more scenic composition manifests parallel decoration as seen on traditional implements such as boomerangs. The rhythm of the parallels animates the hills and trees, which seem to move. A breeze moves the foliage gently. In this painting Richard celebrated the non traditional colours of mauve, green and blue in a composition infilled with sinuous parallels as seen on traditional implements. This scene expresses something of a fantasy, taking parallels to new design levels. The main colours of mauve and green are backlit with subtle yellow to impart luminosity.

This early breakthrough painting is the author’s favourite by Richard. The calm unpainted white of trunks relates to flat sky. The trunks repeat the curved parallels of hills and bear some totemic-like marks. Horizontal stripes and rows of blobs of plain are offset with long parallel vertical leaves of big tree.

Note: Rex’s portrait of Richard pays homage to both Richard’s European derived pink and ultramarine colour systems and to his use of the traditional system of parallels.

Richard later experimented with a new all over system of patterning in which the large tree is painted as a flat part of the design and perspective is reduced. Parallels continue to be important.

Mount Giles, MacDonnell Range, 1948 (watercolour on paper; 28 x 38.5cm; Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory NAM-0161). This was illustrated by Rex Battarbee [2] to show the strong originality of the artist and also his primitive sense of decoration. Battarbee stated that drawing is one of Richard’s outstanding abilities. ‘The flatness of the gum-tree helps his decoration because it forms part of the picture and does not become just a portrait.’

Richard experimented with varying compositional arrangements of the same location, possibly in memory paintings.

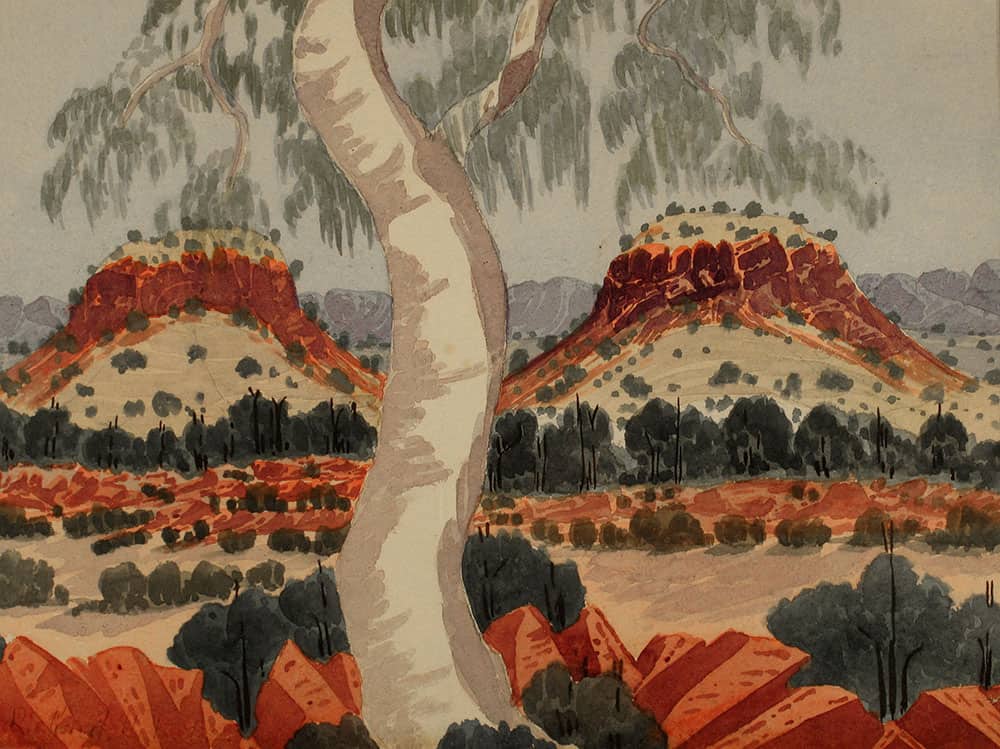

Palm Valley

Richard Moketarinja

• • •

1954 (Native Affairs stamp 28 October 1954)

Watercolour on paper

27 x 36 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-RMo-17

In this composition the artist achieved an unusual view by placing a tree lined up with the space between two hills. An important and ambiguous animate tree, it looks across a riverbed to two significant looking hills. The two feature hills are placed to give a sense of equivalence often present in Arrernte design. This is a relationship painting, linking traditional ground drawing perspectives with European profile perspectives complete with a horizon.

The horizon relates traditional patterning elements to western perspective in landscape painting in which a horizon is usually present. We thus can see how the artist experimented between Arrernte and European perspective imaginatively.

Horizontal rows of patterning lead forward from the two hills to an elaborate foreground screen of geometric pink and magenta rocks, blob trees beneath a curving ghost gum tree trunk, the top of which is cut off from view. There is some parallel vertical line foliage, back lit with lemon. Fine black vertical trunks of foreground trees also sharpen the scene and unite and counterbalance the horizontal bands.

The artist resolved his creation with vertical and aerial perspectives in mind simultaneously, an unusual achievement.

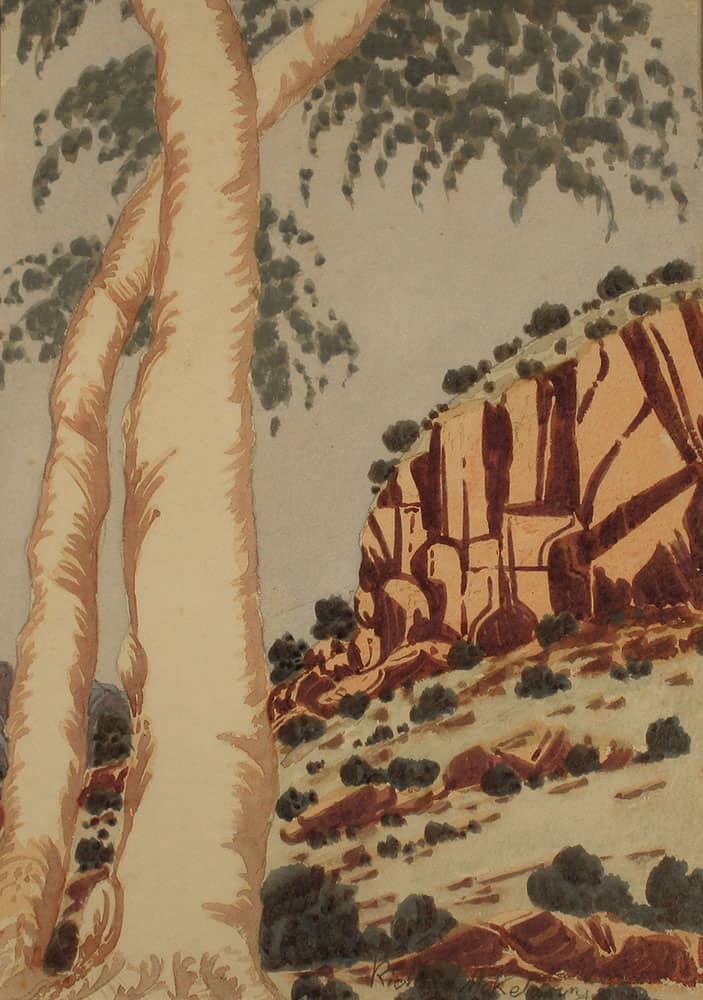

Ghost Gum, James Range

Richard Moketarinja

• • •

early 1954

Watercolour on paper.

38 x 27 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-RMo-08

Here, a pictorial watercolour painting of two mature gum trees in a steep hilly area is surrounded by pokerworked symbols on the wood frame. The symbols demonstrate the cultural attributes of the country on each side from his point of view. Several aquatic creatures are suggestive of Palm Valley after heavy rain. In the painting composition is a profile of a concentric circle low on the larger tree trunk, perhaps suggesting that the tree and place are significant. The subject of the painting is a detail of the wider location referred to on the frame with the symbols of its cultural and locational attributes.

The top edge of the frame is a cross cultural gesture: with a possible symbol of tribal authority at the left end; a southern cross, the moon and sun in the centre; a European profile form of landscape and an apparent aerial perspective diagram like a map of land. On the lower edge a schematic tjurunga and other symbols are at lower right; the sun is at the centre on the lower edge of the frame; and, to the left of these are two Aboriginal symbols.

In this pictorial composition two mature gum trees seem to relate to the hill which is topped with stylised rocky cliffs at right. This is a glimpse of part of a larger and special location. Major areas of the composition are treated flatly including the sky, the white on tree trunks and the pink rock faces which are balanced by busier geometrics and dotting. The pink rock faces are stylised as nature based geometric shapes. The large white areas on tree trunks are unpainted paper. There is yellow on top of the hill and again on the foreground slope.

On the frame, the artist has presented and shared his traditional experience of the attributes of Palm Valley after rain. After rain aquatic, animal and bird life become abundant. The area then became a shared ceremonial area for the Loritja and Arrernte people, while food lasted abundantly for several weeks.

The symbols appear to be a moving visual statement of important ‘things that matter’ across the upper and lower edges. At the side edges is a symbolic inventory of creatures of Palm Valley complete with a ceremonial man in the stance of corroboree dance and some symbols that only ‘those in the know’ might understand and revere.

The artist may have expected non Aboriginals to recognise the symbols for aquatic and land wildlife, but perhaps they are presented to display some aspects of Aboriginal culture, even though we are not expected or entitled to understand the full meanings of symbols. The profile view of the landscape (top right) is in the traditional parallel method which the artist loved to employ in watercolour. The aquatic creatures are suggestive of Palm Valley after rain. One drawing fourth from top on the right side appears to be the shield shrimp (Triops australiensis) found in Palm Valley. There are no apparent Christian references on the symbols.

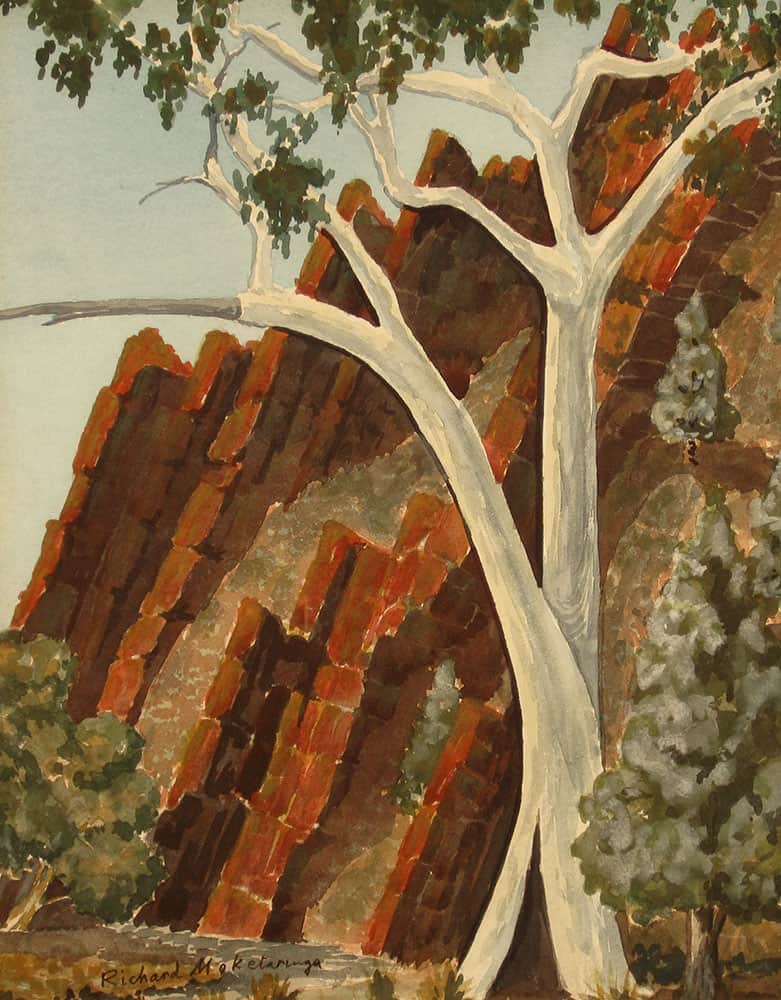

The Organ Pipes, Glen Helen Gorge (Quaraitijnama)

Richard Moketarinja

• • •

est. 1954-55

Watercolour on paper

35 x 28 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-RMo-02

This is a new experiment using dark straight chunky parallels in a scenic interpretation, thus presenting the tree as a contrasting character. This is a different compositional approach with no colour fields. The blue of the sky is the purest colour in the composition. Red ochre geometric parallel cliff with zigzag edges relieved by discreet slopes of blobs over green/grey wash and small trees each side with blob foliage, back lit with pale grey. Dramatic pale grey and white feature tree contrasts with dark cliffs and has muted green blob foliage. Inscribed in pencil: Warren Gorge, near Standley Chasm.

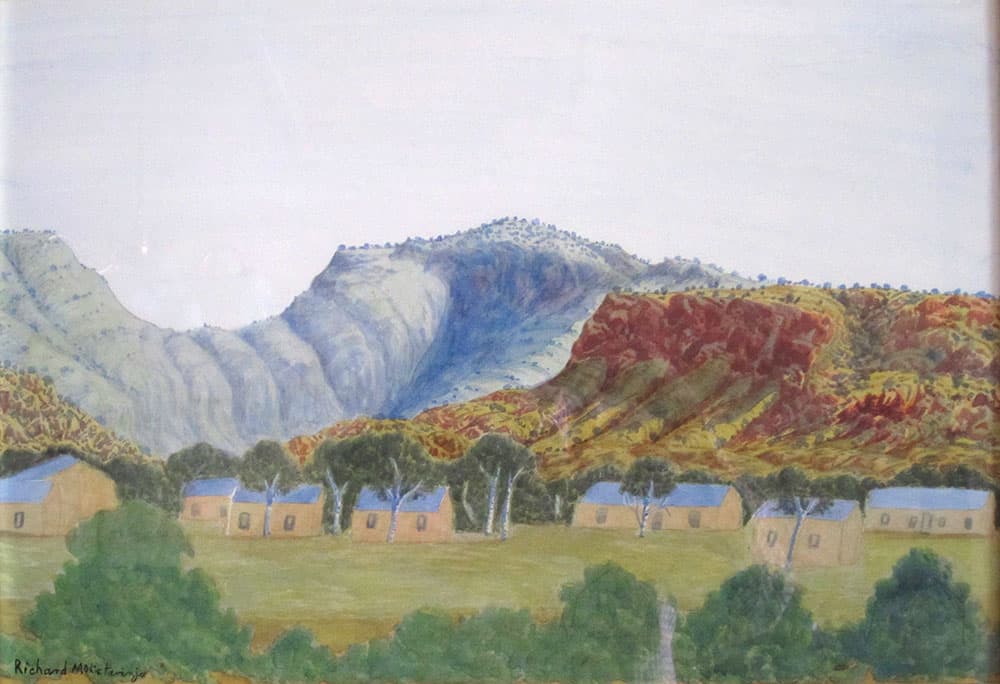

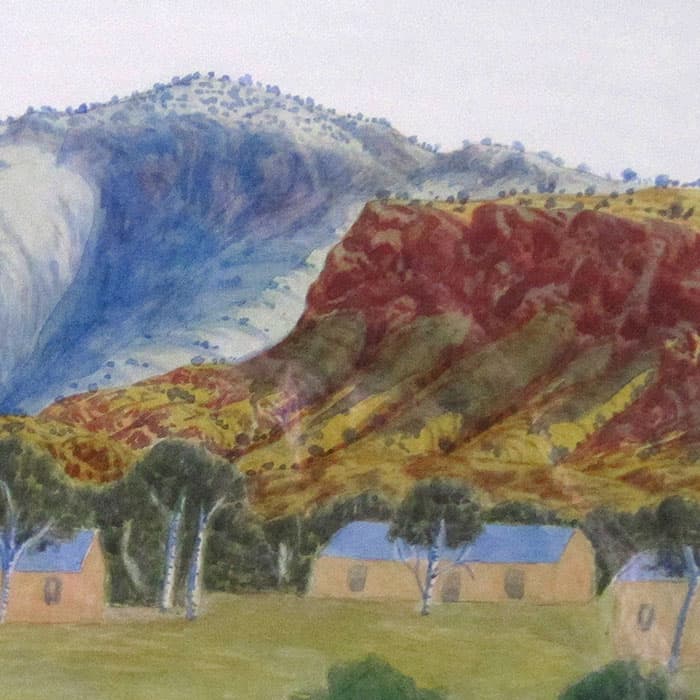

Mt Hermannsburg and the Hermannsburg Mission

Richard Moketarinja

• • •

est. 1960-69

Watercolour on paperboard

36 x 52 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-RMo-21

In this upbeat composition Richard portrayed the Mission buildings minimally and without the detail employed on Mt Hermannsburg and the nearer hills. The country is described decoratively and the introduced non Arrernte built structures are described blandly and schematically. This was created at a time of increasing pride and consciousness of aboriginality, but when life was destabilised through problems of alcohol, access to money through art earnings and the independence related to unprecedented change. There was discord in the Mission community.

From the mid-1960s Richard created glorious interpretations of his country with sweeping views. The author reads these paintings as possibly euphemisms for people (represented by trees) celebrating life in their fantastic country. The artist retained his parallels and zigzag devices as part of varying orchestrated systems to express the excitement and/or dreamlike quality of his portrayals. For Richard the use of certain pigments such as cerulean blue and Prussian blue were a new experience through which he achieved fresh levels of luminosity.

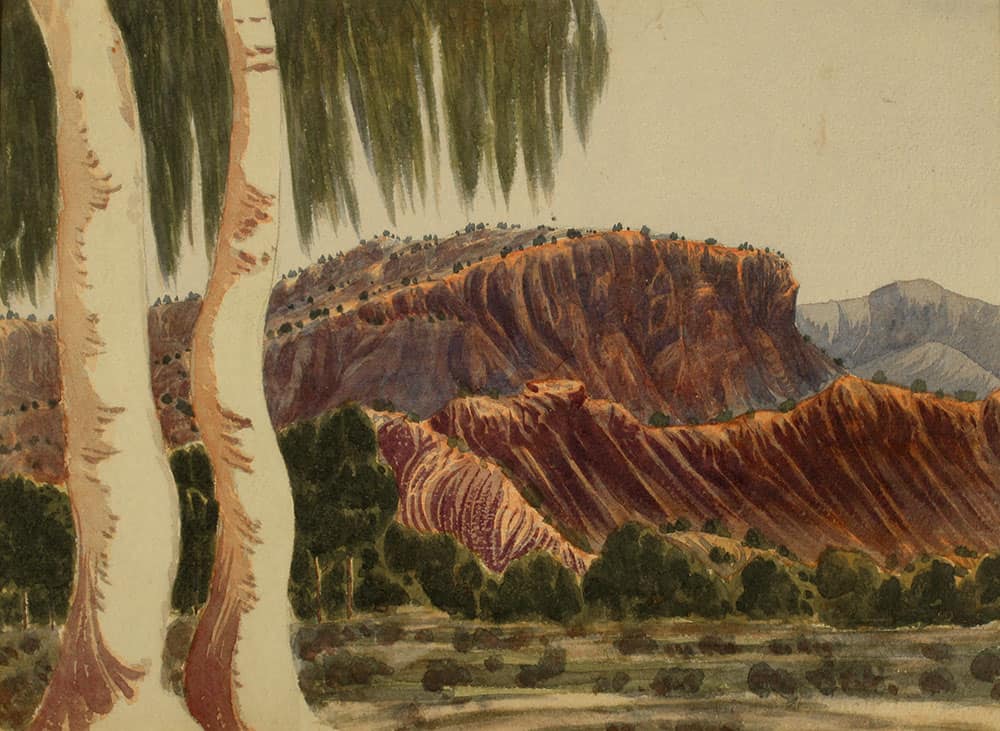

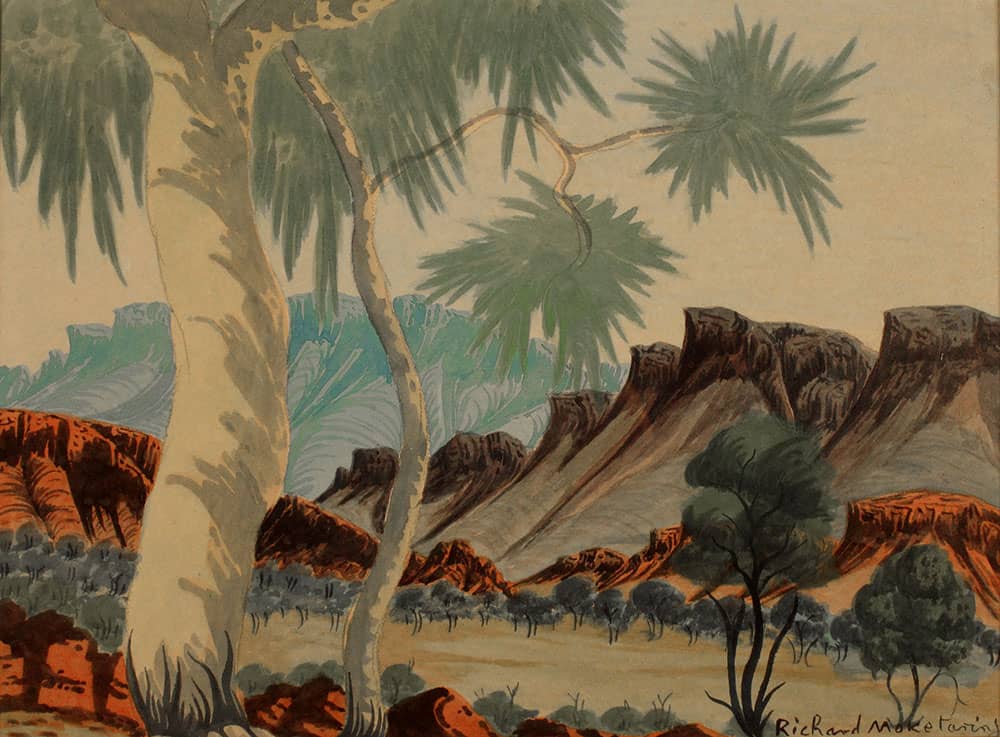

MacDonnell Ranges

Richard Moketarinja

• • •

est. 1960-69

Watercolour on paperboard

26 x 35 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-RMo-01

The two white-trunked big trees at left are in a slow rhythm. Right tree trunk is sunlit from the right and the left tree appears to be lit from the left in a kind of symmetry. The sense of fantasy in this painting is heightened by the exaggerated large leaves on the big trees. The small black trunked tree at right foreground is like the other small trees on the plain; so do the black trunked trees represent the ‘ordinary’ people of the tribe?

The hills on the right side have stylised zigzag tops of dark greyed purple and the mid-ground red low hills have short vertical parallels on tops and curved bases with lateral parallels. Palest cerulean flat sky and three tone coloured distant hills, round bases and described with lateral parallels. Zigzag totemic marks on lower right tree trunk and diagonal curved parallels on left tree trunk are like totemic marks. Red hills screened by blue blob trees with fine black curved trunks. Pale plain balances sky. Foreground screen of red rocks and blob foliage behind two totemic trees and two small black trunked blob trees. The left tops on the distant blue hill echo the zigzag shapes on the right hand hills. Pure colour washes were applied first. Yellow was used on the plain, tree trunk and behind foliage to enhance luminosity.

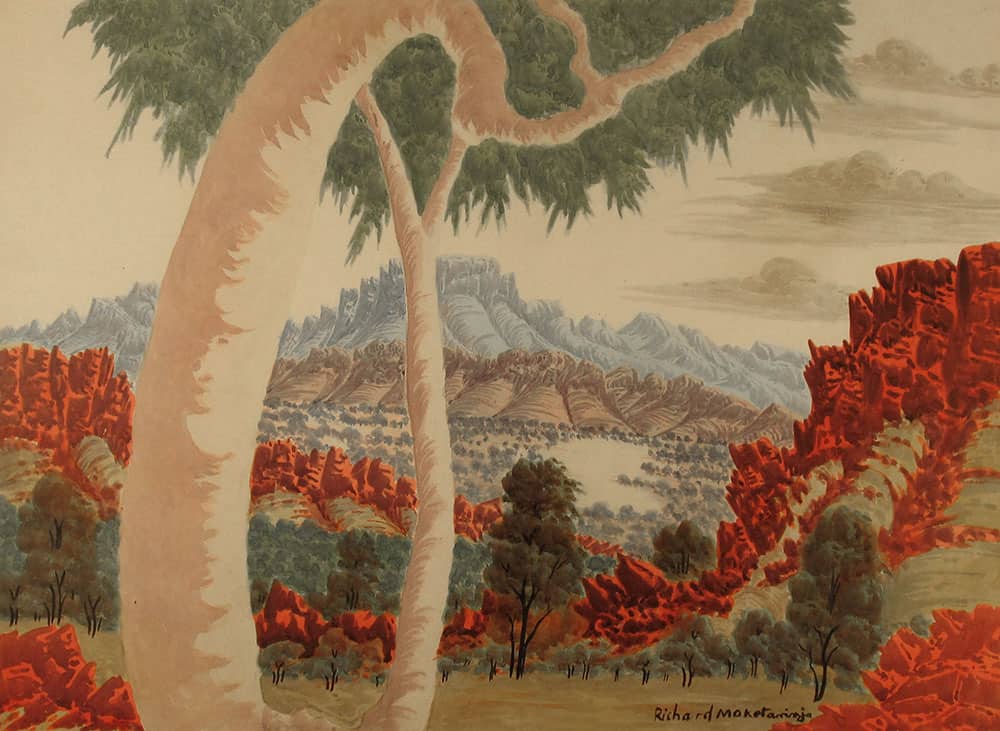

Desert Hues

Richard Moketarinja

• • •

est. 1970-78

Watercolour on paperboard

53.5 x 74 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-RMo-11

This portrays a rocky country which is described in intense detail and yet is balanced by areas of calm, especially the overarching big tree, the sky and the pale yellow area of the plain. All of the small trees are subordinate to the totemic country.

This is a very animate and dramatic scene. The viewpoint is from up high, looking across the plain to the important hill in the distance, which is screened by well described foothills (like Elton Wirri). The composition is horizontal at the bottom. Although this painting has well developed recession, every part of the topography is important. The rear plain slants down to the right (like Ewald’s practice) and has soft blob infill. There is a refined all-over system. Intense areas are relieved and united by areas of calmness. The flat almost colourless sky is in-filled by soft clouds at the right, which relate to the curvy tops of foothills and blob trees. The flat cloud bottoms relate to the muted horizontals in the foreground. There is calmness in the big tree and unpainted white on plain. The opaque yellow over-painting on left and right hill bases and foreground achieves a ‘calming’ luminous effect.

REFERENCES TO EXTERNAL TEXTS

[1] Sir Baldwin Spencer and F.J. Gillen The Arunta: a study of a stone age people. Fig. 232 [2] Rex Battarbee Modern Australian Aboriginal Art