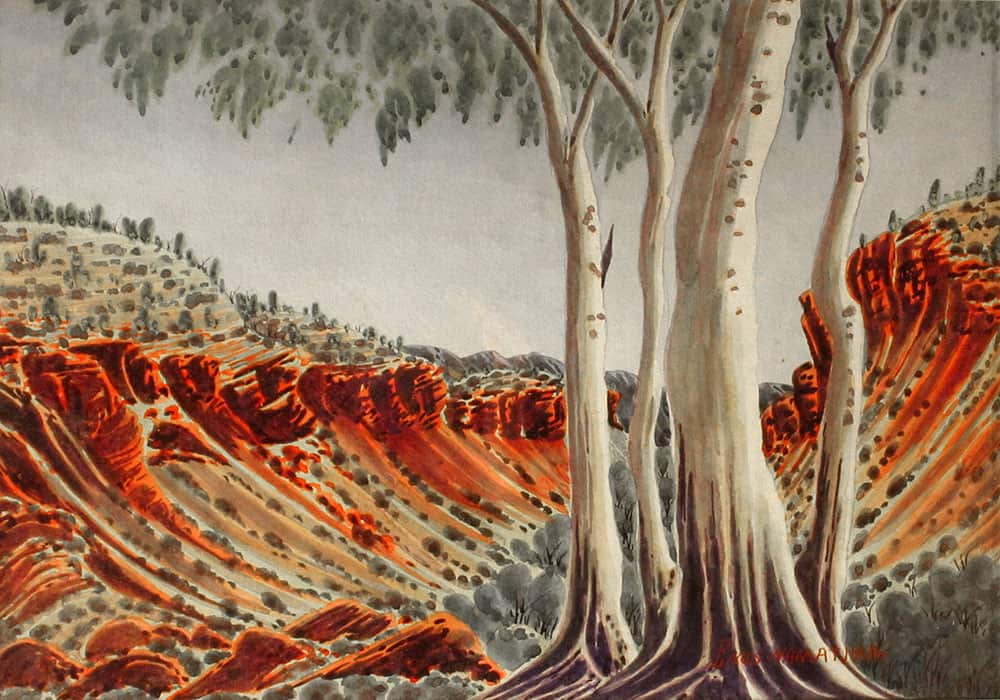

Stunning Aboriginal landscapes lit up the lives of white Australians during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

Following World War Two, this was a period of national uncertainty and a heightened sense of Australia’s isolation. The romantic style luminous watercolour landscapes on paper were from Central Australia west of Alice Springs.

They were created by young Western Arrernte men in their tribal area of Ntaria, known to the general community as the Hermannsburg Mission.

The first exhibition of the pioneer Albert Namatjira was held in Melbourne in 1938 and sold out. Close tribal relatives joined with Albert between 1943 and 1947 to start their careers seriously as founders of a spectacular art movement.

Ormiston Gorge

Enos Namatjira

• • •

est. 1945-50

Watercolour on paper

24 x 35 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

The Hermannsburg School consolidated with broadened participation from 1949 to 1955, including two women. Their animate portrayals of stone topped hills, gaps and beautiful gum bordered creeks contradicted popular perceptions that Australia was only a lifeless desert at its centre. Energy seemed to emanate from the hills, the red rocky outcrops and the luminous plains. Marvellous ancient white trunked gums often presided like guardians.

Australians were surprised to experience directly the unprecedented outpouring of talent from numerous artists of a small and remote Indigenous community on a scale per head of population exceeding that for which any large white community would have been proud. Ntaria numbered only a few hundred people from babies to the aged.

From 1943 to 1960, some 60 young Arrernte men and two women joined with their tribal relative Albert Namatjira to form a distinctive Australian watercolour landscape painting movement. Half had careers as artists, while the others tried their hands or painted occasionally. They were born between 1902 and 1942. It was actually a movement for men, but in the 1950s two women painted with their husbands, one having a significant career and the other a limited career.

Cordula Ebatarinja asserted herself to become the first Australian Aboriginal woman to have a significant career as an artist. The movement reached its height in the 1960s with a resurgence after the drama and death of Albert Namatjira in 1959, but it lost its momentum in the 1970s.

The research and this manuscript arising from it is important because the popularisation of the Central Australian landscapes involved the first major art engagement of a small and unique Australian Indigenous community – Ntaria/Hermannsburg – with the contrasting general Australian community beyond. The author has charted a complete record of the years of activity of each artist. This manuscript comprises a complete representative record of the art.

See abbreviated Activity Chart and pattern of development of the Hermannsburg School.

Part One of the manuscript is about the background and circumstances which created the unique setting enabling the art to emerge. In the Christianised Arrernte mission community large bible pictures demonstrated the ‘truth’ of the Christian message by depicting the Crucifixion, for example.

Part Two is about the stages of development of the Hermannsburg School from its foundation in the 1940s, its consolidation in the early 1950s and its resurgence and redefinition in the 1960s and 1970s. The work of each of the artists is discussed in the order in which they started to paint seriously. Part Two presents the art of the pioneer Albert Namatjira and the other eleven founders, how the art movement and its success changed the circumstances of the artists and their relationship within the Mission community at Hermannsburg. Part Two continues by presenting the work of new artists emerging at the time of consolidation from the late 1940s to 1955.

Part Two then describes the resurgence in the 1960s of the Hermannsburg School after the drama and tragedy of Albert Namatjira in 1958 through 1959, ending with Albert’s death. The 1960s was the busiest period for the movement while the art became a dynamic in the rising consciousness of aboriginality. After 1960 many of the artists lived in Alice Springs town camps, while their wives and children lived at Hermannsburg. One of the artists became a major leader of the land rights movement in the 1970s.

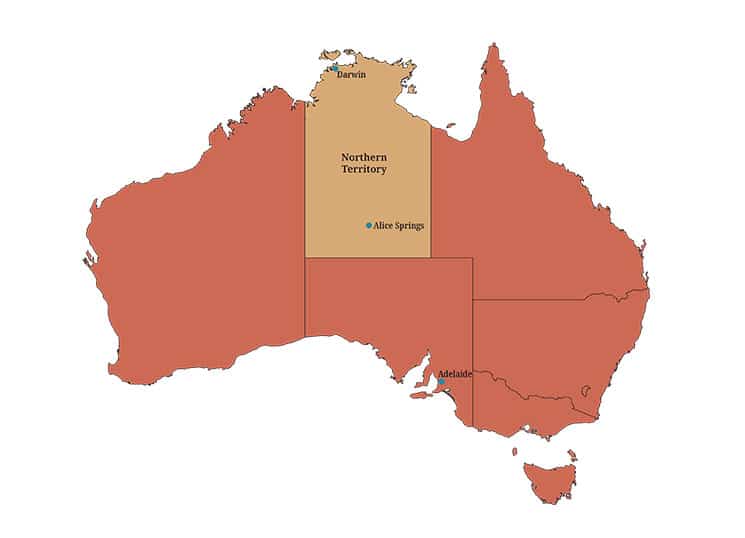

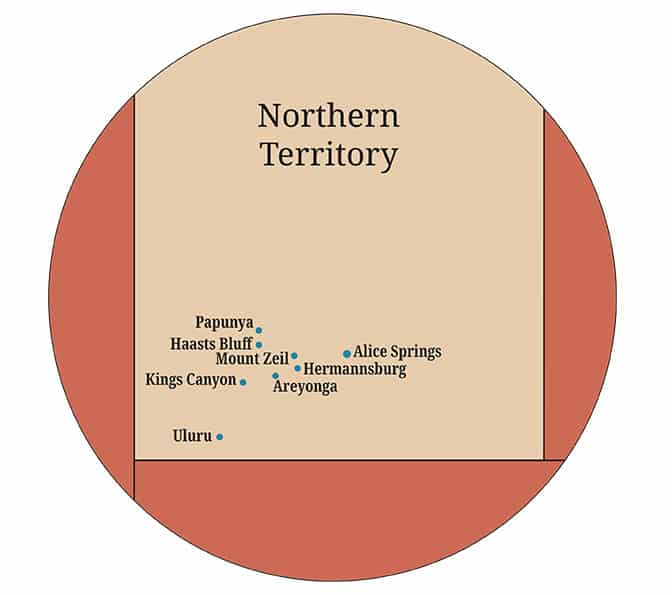

Reference: Hermannsburg and surrounding areas

Part Three about evaluating the Hermannsburg School involves charting the artists years of activity, discussing the wider effects of its success and describing the distinctive methods of painting.

There were problems with the acceptance of the paintings in the high art world. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s the art could be read as assimilationist by those so inclined without appreciating the powerful cultural integrity of its purposes. Contemporary scholars and critics at the time of its popularity were not trained to assess Indigenous modern artworks that were not made for traditional purposes. As the descriptive landscape art then appealed to middlebrow tastes it was not always appreciated as a genuine art of emotion from a particular cultural perspective.

The author argues that the Hermannsburg School should be accepted as both a romantic and a modern art. It was a genuine art of emotion – as valid as the romantic expressionist art of the acknowledged Australian modernist artists notably Russell Drysdale, Arthur Boyd, and Sidney Nolan.

The Hermannsburg School ran into problems of acceptance at a time when “The anthropological view of Australia as an ancient continent peopled by an unchanging indigenous culture (the post war European Australian shorthand for this being ‘The Dreaming’) was to undo European modernism in Australia as successfully as the eighteenth century artists who valued the antique more highly than contemporary technologies.” (Paul Fox Landscape as art: Modernity and its Australian Histories. Catalogue essay The Modern Landscape 1940-1965. Museum of Modern Art Heide. 10 March-3 May 1998). In other words, anthropologists could not accept that Indigenous culture might be dynamic like all other sectors of culture.

The Hermannsburg School artists coped with the modernity of roads, towns and objects usually by denying their existence and omitting them from their paintings. In discussing Australian modernism, Bernard Smith made the point that expressionism in Australia, being a romantic art, had no great difficulty in establishing links with popular culture. Smith also observed that “Art styles and their appreciation cannot be separated from life styles; and of course all life styles in Australia are not similar.” (Smith 1991. P 347).

Ntaria/Hermannsburg should be recognised for what it had become, that is an idiosyncratic and unique dynamic Indigenous culture that was firstly both Christianised and traditional with the cultural fusing having evolved over decades. Anthropologist Diane Austin-Broos concluded that the Arrernte became Christian by rendering Christianity in an Arrernte way (DA-B p 86). Second, the community had acquired some modernising technology as with the water pipeline from Koporilya Spring.

The employment of some forty Western Arrernte men in the army labour force in Alice Springs during World War Two (1939-45) was seized upon by a few as an opportunity to decorate quickly produced souvenir artefacts for sale to American and Australian servicemen stationed in Alice Springs. Around Hermannsburg many mulga trees were cut down to produce replica boomerangs and wall plaques on which were painted animals, plants or symbols. Richard Moketarinja, for example, was keen to earn money in his spare time to send to his wife in Hermannsburg.

In this fused culture it should thus be accepted that the pictures being created for an external market were, from an Arrernte perspective, their visual poems of ‘truth ‘of the creation and their ancestral country.

In this manuscript readers can enjoy the progress of human and artistic development of each artist individually and as members of a movement of artists who were mostly blood relations. Through these paintings the artists reached out and in turn responded somewhat to the desires of the market they created.

The artists and their public experienced aspects of the space between their cultures in an unprecedented way. They adapted a familiar European based visual language to bridge the perception gap and express their feelings and display their knowledge and distinctiveness.

The author tells the story from her own perspective as one who experienced the Hermannsburg School from her teenage school years in Melbourne in the 1950s. Concluding that the School deserved special study, decades later she compiled methodically a considerable collection of the work of each artist over more than twenty years. She writes as a social scientist (with some undergraduate anthropology study) and with a background in fine art history study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS BY THE AUTHOR

I have received encouragement and guidance from several people during the last 16 years, while assembling my collection.

Professor Terry Smith, then Director of the Power Institute in Sydney and later holding prestigious overseas professorial posts in Art, who first saw my collection and offered advice as to future purchases and direction of my research. Years later he visited again to view the then much larger collection, my early research and analysis, and provided confirmation and encouragement to continue and to commence writing my manuscript.

Professor Chris McAuliffe, then Director of the Ian Potter Museum of Art at Melbourne University, and his colleague Joanna Bosse, also visited and provided helpful advice.

More recently, Professor Ian McLean of Melbourne University read my draft manuscript. He has been very helpful and encouraging.

I am most grateful to all these people.

I also acknowledge the important help provided by the National Gallery of Australia, Flinders University Art Museum in Adelaide and Professor Vincent Megaw, the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory at Darwin and at Alice Springs, and the National Gallery of Victoria. Each of these major galleries provided excellent access to their collections of Hermannsburg paintings for my research, which I have been able to study and use in my analysis and estimation of dates of creation of the paintings. I refer in my manuscript to many of these paintings, but at the Galleries’ requests, have not included images of these paintings.

I also wish to acknowledge the help provided by Alison Boldys, early in my collecting phase, in setting up my collection index and register, and other computer programs for organising and recording the collection.