1930 – 1984

Ewald Namatjira shared the robust shades of his emotions in the way he showed us his country. His passionate intelligence powered his precocious creativity. By 1950 he portrayed an animate country and from 1960 he became assertive of his Aboriginal heritage. Ewald was a founder and master of the Hermannsburg School. He was a very interesting, dedicated and important painter.

Ewald avoided the schoolroom and other Mission work, stating that he did not feel well enough. Rex Battarbee thought he was somewhat delicate. In June 1938, when Rex Battarbee was camped with Albert 3⁄4 mile from Glen Helen Gorge, Rex Battarbee noted in his diary (23.6.38) that ‘Enos returned with Evolt [Ewald] and that Albert seems to be very fond of him’. Ewald would then have been almost eight years old. Thus, for his education, Ewald spent his childhood and early teens mainly out bush with his father at painting camps.

The Mission did not apparently have high expectations of him but he was obviously passionate about painting and the atmospherics of the Finke River valley area and far beyond. He seemed to thrive with painting from the time he began.

As the third of five sons of Albert Namatjira, Ewald started to paint seriously in 1947 when aged around 17. From the beginning of his career in 1947 as a 17 year old, his expressive paintings show unusual creative capacity and engagement with this work. Painting seems to have given him personal confidence, which shows in his emphatic and sometimes extrovert signatures as well as the art.

Ewald usually painted when in an upbeat mood; but in some he demonstrated an OK state or a sense of equilibrium and in a small number expressed less than happiness and even anguish. Ewald adapted well from the trauma of losing an eye in a traumatic gun accident in 1949 to overcome the visual disability to achieve his finest paintings. Regeneration, rather than hopelessness, was his message.

He was a prolific and enthusiastic painter and, perhaps understandably, a number of paintings appeared to be quickies aimed to sell, perhaps to passing tourists at moderate prices. Many of these quick paintings were moving and joyous when he was fully engaged.

Ewald was Western Arrernte, Subsection (Skin) Peltharre. Ewald married Eubia (a Pitjantjatjara woman), sister of Thomas Stephens Tjapangati, also known as Thomas Stephens (who painted in watercolour tradition). Thomas was a younger brother of Eubia and apparently lived In Papunya [Heritage of Namatjira]. In 1957 Ewald and his wife were living at Areyonga, south west of Hermannsburg, with their three living children. However, in the Census of Wards for 30 June 1966, Ewald and Eubia were at Connellans, near the airstrip outside Alice Springs.

In the 1960s he seemed stridently assertive of his aboriginality, including through his increasingly conspicuous and decorative infill patterns. These infill patterns were first employed to appear as dot trees and diamond like foothills. Ewald came to the height of his powers in the 1960s.

Ewald continued to develop through the 1970s, but no work has yet been identified from the 1980s.

As a late teenager, Ewald demonstrated an unusually sensitive capacity to engage with the landscape and its atmospherics. For example, he created several interpretations of a hill of interest in the Ormiston area.

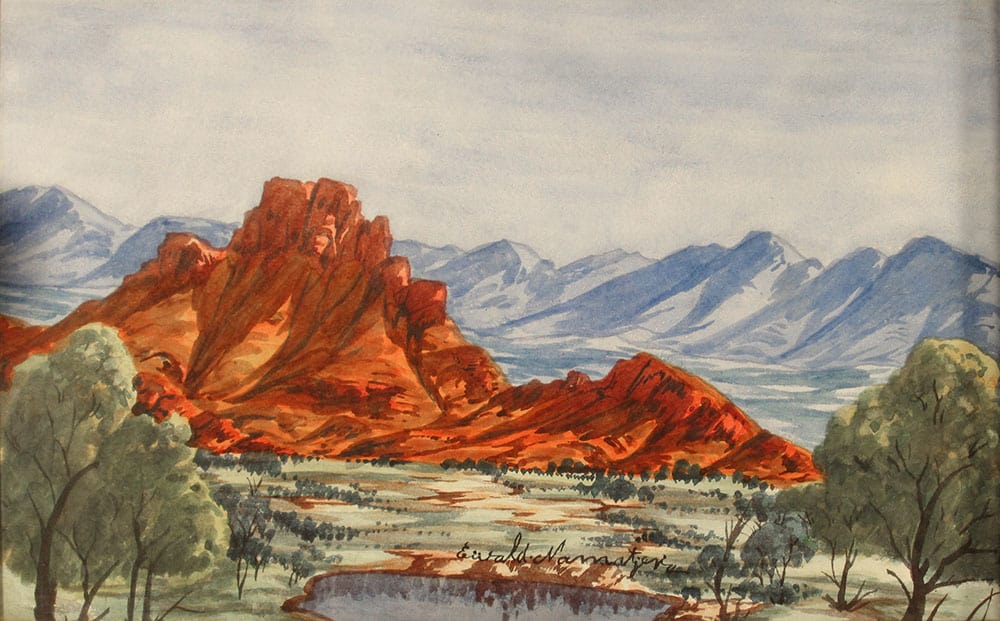

Central Australian ranges Landscape (inscribed verso: Ormiston)

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

est. 1947

Watercolour on paper

26 x 36.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN- 37

[Note: the surname is misspelt as either Namijiiaia or Namatuaia. This is from Gordon Simpson’s collection, having been lot 9 in Theodore Bruce Adelaide auction Monday 20.6.2010. This is the earliest Ewald that the author has seen.]

In this painting the artist was fully engaged but not upbeat. The painting is slightly faded. The right side of the mid ground hillside at left of the painting has an unusual pale blue wash on its downward curves, catching the light. There is a small area with palest lemon yellow under wash on the centre of the front plain. In this work he seemed to be learning to know how and perhaps what to describe about this hill and was possibly a bit daunted by the challenge. He persevered successfully.

The second version of the hill is Untitled, 1947 (watercolour on paper; 19 x 21cm (irreg.); Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory NAM-0199). Illustrated on front cover of Heritage. This composition is more upbeat than above and describes the hill and foreground more positively.

Third version of the hill is Landscape, c1950s (watercolour on paper; 26.4 x 37.4cm; AGSA 0.172). The author estimates that this was painted in the period 1947 to 1950, and most likely in 1948. In this stylised interpretation, Ewald has advanced in summing up the scene and added the two trees at left last, perhaps to alter the perception of space and to engage with the market.

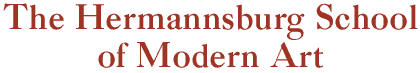

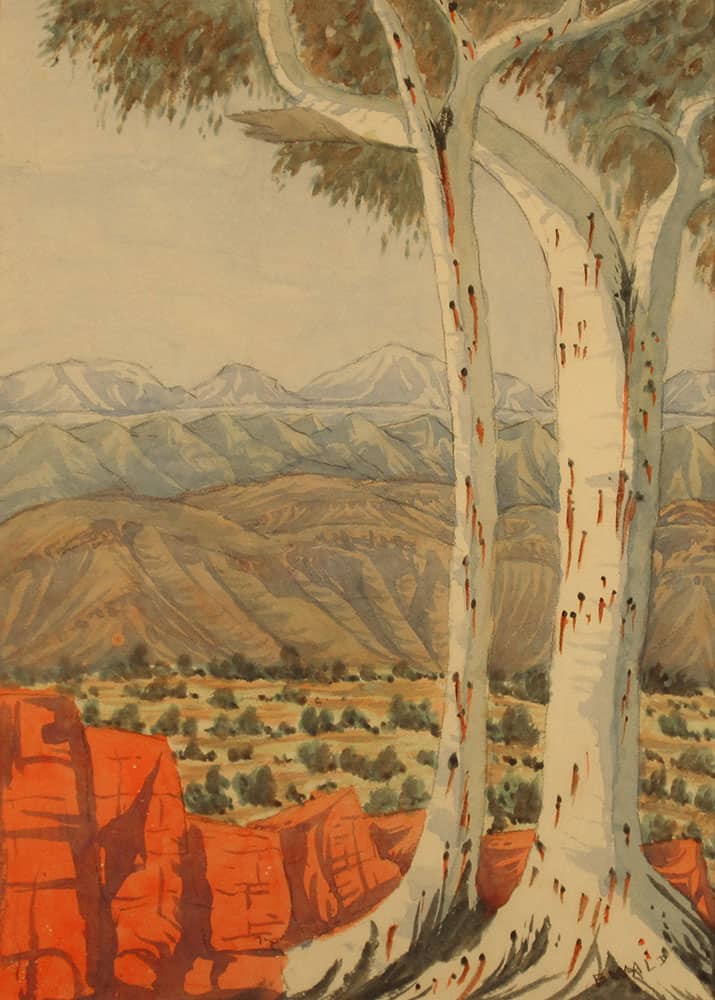

The tree

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

est. 1948-49 (when aged 18 or 19 years)

Watercolour on paper

36 x 25.7 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN–19

This early masterpiece is serene and quietly upbeat. The basic concept was marked lightly in pencil. The sophistication of this delicate and complex work established Ewald’s potential as a fine artist.

In this painting Ewald has moved on from his achievement in mastering the particular hill, which was the subject of the previously discussed three paintings.

He analysed a new challenge here, one of describing a vertical landscape with seven rows of horizontals to achieve distance:

1. Large red geometric rocks;

2. Yellow plain;

3. Front range of hills;

4. Mid-range of hills with geometric interest;

5. Rear strip of plain;

6. Distant hills;

7. Sky.

Each area of the horizontals relates to the overall system. The subtle tonal changes in the pale blue of the sky, distant hills and on the tree trunk help tie the composition together.

Ewald suffered a gunshot wound to his head in (October?) 1949, when (aged 19 years) he was playing with a gun, while out at his father’s painting camp at Areyonga. He survived but lost his right eye in the operation attempting to remove the bullet from his brain in Alice Springs Hospital. Rex Battarbee stated that he suffered greatly from the after-effects of the accident, but rose above the disability to paint many works, which may be considered his masterpieces (1971).

Despite the trauma, Ewald appears to have adjusted well in painting with his left eye only after this sudden loss. A survey of scholarly medical literature demonstrates most people who lose an eye fairly early in life, rather than in old age, adjust well and most of them within one year. Ewald would have had approximately a 20 – 25% decrease in the size of his field of view (peripheral vision) and probably an enhanced contrast sensitivity in the remaining eye compared with people with both eyes. Minimal adjustment would have been needed to accommodate distance and perspective. For painting, he would have adjusted for peripheral vision loss by aligning his body slightly and turning his head away from the side of the lost eye so that the good eye centred on the scene being painted. [1]

While adjusting to his loss of peripheral vision, Ewald created Hermannsburg Watercolour, est 1949-50. (watercolour on paper; 37.4 x 26.4 cm; NGA 13362 2000.474).

This vertical scene of a rocky hill, a tall gum tree and a sky with clouds has no depth of perspective. This was possibly created in the year after the accident, while Ewald was adjusting to his acquired monocular vision. No depth was attempted in this painting by way of distant hills and the vertical composition did not require peripheral vision.

It is a relatively tonal painting and has two areas of pale under wash, one for the sky and the other for the hill. The scene is described rhythmically with small curved marks relating to small straight geometrics. The mood of this painting is one of equilibrium, perhaps on the downbeat side. The resolution of this must have been reassuring to Ewald.

In the same year as the accident, Ewald painted Flame-like Mountains: James Range in a location close to the scene of the accident. This dramatic painting seems to show something of the process of visual recovery, if not yet emotional recovery from the trauma. There is no depth in the painting and it is a vertical composition, not requiring peripheral vision. (Heritage… Fig 4.15 in Gayle Griffiths and Robin Battarbee Collection at Araluen Museum at Alice Springs).

As described later, in the years following the loss of his right eye, Ewald’s landscapes slanted emphatically down to the right, in what the author thinks may have been partly a visual adaption to the loss, but the slanting horizons may also have been an aesthetic choice. The slanting suggests movement in the landscape and most of his landscapes appear animate. In some he combined horizontals in one part and slanting elsewhere in the same painting.

The rocky hills in Central Australia are rich in nature based geometric patterns. After the accident injury Ewald returned to his interest in geometrics and took nature based geometrics further in a stylised form, relieved with curves.

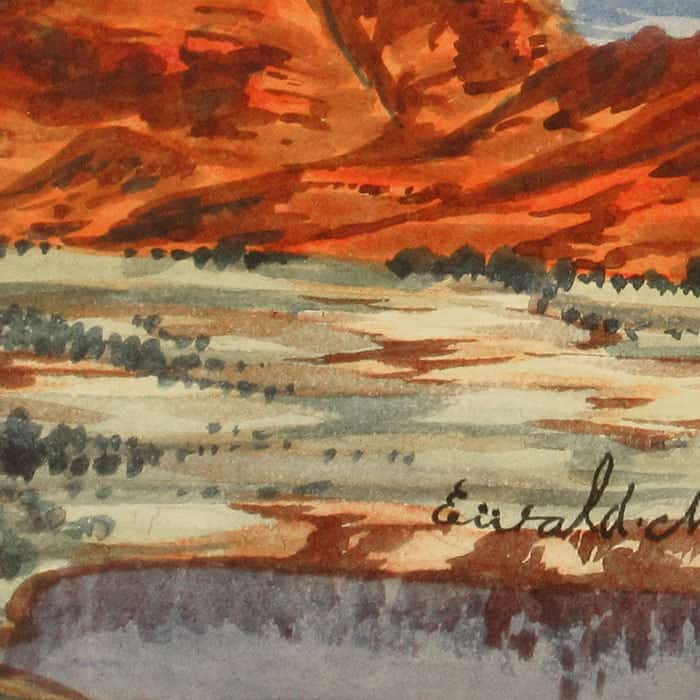

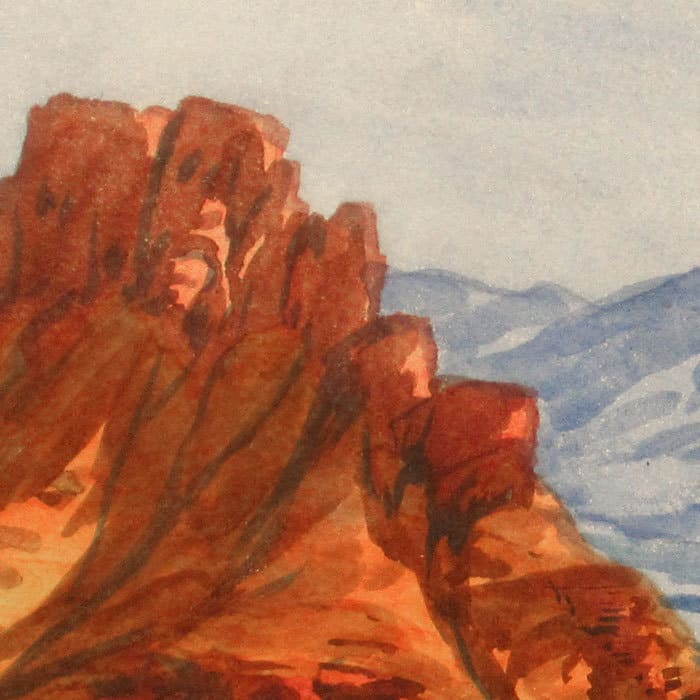

Central Australian landscape

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

est. 1949-50

Watercolour on paper

26.5 x 37 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN-23

This is a contrived geometric composition, relieved by curves. The large signature in pencil shows confidence and ‘attitude’. The painting is upbeat and vibrant. Ewald did a number of paintings involving nature based geometrics and relaxed geometrics. Softening the emphasis on geometrics, Ewald then explored the interplay of curves and parallels with geometrics and straight lines in a subordinate role. Location: Mt Giles is the possible distant mountain.

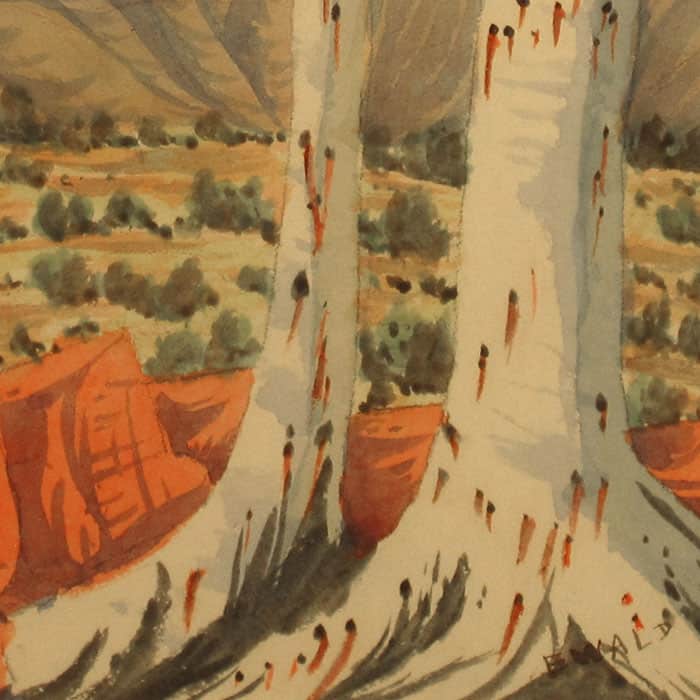

Rain Clouds, MacDonnell Ranges

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

1954 (approved for sale Mar 1954)

Watercolour on paper

28 x 38 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN-31

There are two mindsets in the painting, which was done over two occasions. In the first conceptual sitting the profile of the distant blue hill and big hill and foreground were lightly pencilled in and the distant blue hill was painted carefully in one colour. On another day the looser and rhythmic composition was completed together with the rainclouds. More energy and emotion is evident in the second and main part. Note: another painting had been started on the other side and abandoned prior to this composition. Ewald may have tired after starting the blue hill, returning to it when more engaged.

This breakthrough painting was an important precursor of Ewald’s early all over system based on curves with parallels with some straight line parallels and geometrics. It anticipates the loop system of the 1970s.

Totemic Hill

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

1960 (purchase authorised 11.3.60)

Watercolour on paper

34 x 54.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN-26

This is the author’s earliest dated Ewald which has a conscious indication of diamond infill, but it is disguised as landscape, after the method of his father. Thus it marks a pivot in a turn to a new mindset in which the ‘diamond’ pattern later became an overt statement in later paintings. This area in front of the hill was painted carefully in a different mind-set to the distant blue area of the composition.

Location: This is the important hill often shown at Heavitree Gap type of location.

The highest part of the hill is stylised, squared and angular with an apparent face. The lower right end appears natural. There is no foreground barrier or screen. Hill bottom and horizon slope downward to right. Distant hills merge with blue infill of rear plain.

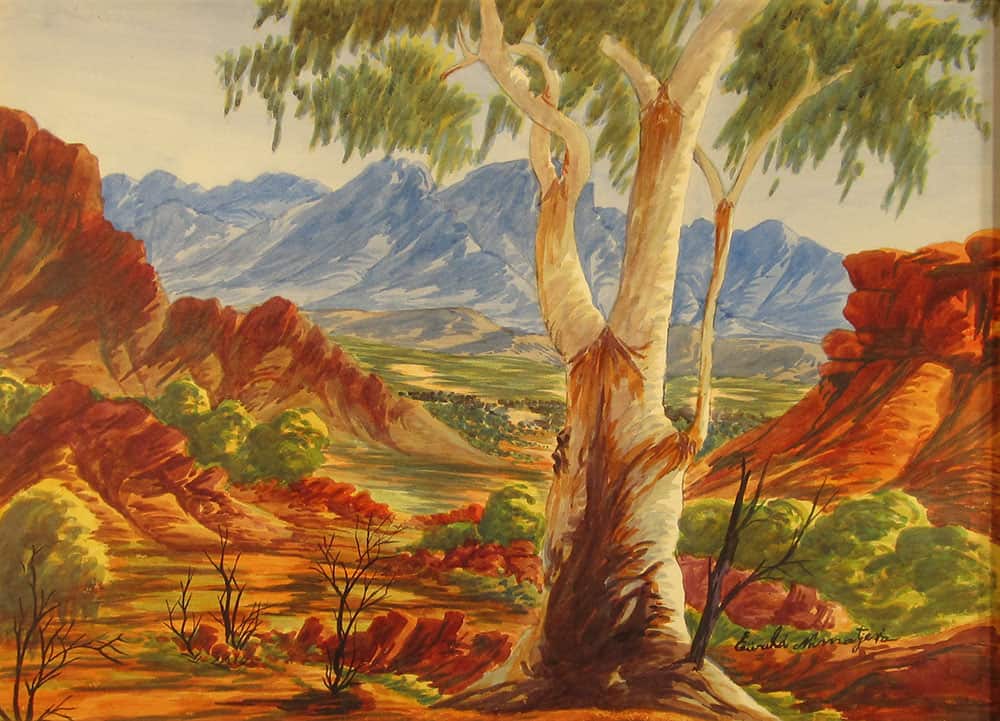

Central Australian landscape

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

est. 1960-62 (5.10.6 authorised stamp)

Watercolour on paperboard

51 x 72 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN –24

There is something ambiguous about the totemic looking tree, which presides on high ground above a vibrant world between it and the gap. This major work was created during the resurgence of the Hermannsburg School following the drama and death of the artist’s father Albert in August 1959. This is a ‘memory’ type painting in that aspects of Heavitree Gap and the rocky structure of the totemic hill have been rearranged somewhat to achieve this idealised view of a site devoid of introduced structures.

This composed view is apparently looking north-east through Heavitree Gap, toward the area of Alice Springs town (Mparntwe) side of the gap. The built structures of the road and railway line are absent and are replaced by an elaborate dominating tree. The ‘totemic hill’ through the gap at left, was the subject of Totemic Hill, painted in 1960 and illustrated above. This hill seemed special to Ewald and he has shown it as being higher than the cliff on the right side of Heavitree Gap.

The elaborate tree is backlit from the right. The fantasy view of the area between the hills and big tree seems lively. The rocky outcrops and blob trees, are on a space sloping down to the right and appear to be moving to the right. So the front plain slopes downhill to the right, while the rear plain is somewhat more horizontal (while sloping a little).

The distant hills and pale sky are described in cobalt blue. There are patches of pale cream/yellow on the rear plain. Patches of lemon yellow towards back of front plain. Lemon lights the big tree foliage and animate mid-ground blob foliage. The small tree on left may be bending in wind from left, but the foliage of the higher big tree appears blown slightly from the right. Rear plain has irregular lines of dots at front, immediately behind gap. Line pattern strip behind dot pattern strip, back to low foothills.

The author does not think that there is a monocular problem with distance, as Ewald described the distance in this painting eloquently. The angle of light on the tree conflicts with the light on the hill at right. But then Ewald sometimes used light or shadow for compositional effect. In the June 1966 Census of Wards, Ewald and his wife Eubia were camped at Connellans, near Heavitree Gap at Alice Springs

Central Australian landscape with ghost gum

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

est. 1965-75

Watercolour on paperboard

53.5 x 75 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN-20

In this upbeat painting all of the country appears to be alive, from the hills and the plain slanting down to the right side of the composition which thus appears to be moving to the right to the animate foliage which is like a group of people moving to the right. This very animate composition features a prominent band of overtly traditional infill patterning across the plain. This relaxed ribbon of lines of dots in a diamond pattern may equally be perceived as natural topography or contrived pattern.

Unusually, the signature is unobtrusive and quiet. The location is possibly a generalised location. Animate background cobalt blue hills slanting to right. Animate foreground red rocks, leaning to right. Yellow/brown blob trees appearing to be travelling to right.

View with ranges and clouds

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

est. 1970-79

Watercolour on paperboard

236 x 55 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN-27

Possible location: Looking south near ‘Ewald’s totemic hill’ with a cliff of one side of a gap in the distance. This demonstrates the artist’s enhanced contrast sensitivity, acquired after his loss of one eye as a teenager.

This major work has two trees at left standing in a slight breeze in front of a flat horizontal row of animate lemon and green vegetation, with a flat based screen of cadmium red rocks behind, dramatically introducing the scene behind. The two plains glimpsed behind slant down to the right in keeping with Ewald’s approach involving animation. The crimson/pink rocky totemic hill structure exists between the two plains, which are merely indicated. This totemic structure has faces on the central ‘rocky hill’.

Clouds riding over the scene also serve as striped infill, arranged to repeat the slanting qualities of the plains. Rocky areas, including the blue hill, appear to be relaxed geometrics. The author considers that Ewald relaxed the geometrics and loops in order to achieve animation.

View through the valley

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

est. 1970-79

Watercolour on paperboard

37.5 x 49 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN-28

Emotions triggered this passionate and downbeat cry from his heart. The regenerating foreground vegetation is struggling but ‘hanging on’ with some optimism. The hills and foreground rock area appear active. This painting demonstrates enormous force of character on the part of the artist.

The foreground seems to represent Ewald’s sense of self; the yellow/orange plain is the bereft world between the foreground and the mountains which seem as if they are going on regardless.

This ostensibly portrays a scene of regeneration as if after a fire, viewed from behind a low symbolic screen of a red rocky outcrop. The tall black tree has foliage on top limbs, but not the lower limbs. It is touching that the dead side limbs curve gracefully and with the foliage give some hope to the scene, and hope and faith that the situation is not irreparable. The way down the hill is barred to the viewer, or outsider, by two black stumps leaning to touch each other symbolically – most unusual. The trees behind the animate red foreground rocks are also animate. Front plain glows orange, back plain muted magenta dots over lighter muted plain. Heavy screen and black tree and stumps seem to suggest pain – and seem to cry out: ‘leave us alone’ or ‘things must change’!

The general system of looped hills and relaxed geometric diamond infill integrates with the loops. The two straight touching black stumps contrast starkly. The infill pattern is important in design – the plains have no defined trees, only the dots forming loose geometric diamonds (for the infill).

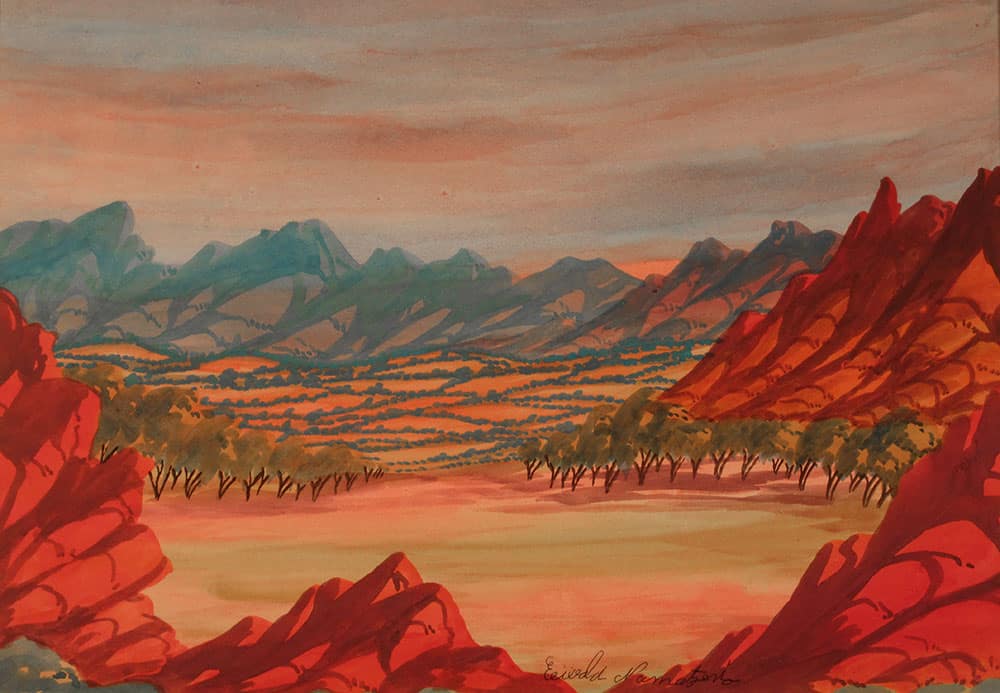

Mountain Range

Ewald Namatjira

• • •

est. 1970-79

Watercolour on paperboard

37 x 54 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-EwN-22

The location could be the same as that in the despairing View through the valley, but this expresses a rosy view of life. This painting is happy and upbeat and playfully reverses his normal right side downward slanting by slanting the horizon down to the left.

As usual, the foreground is on a flat base. However, in a new approach, the sky curves down to the horizon in the centre.

This glowing sunset scene is somewhat loopy and has some gestural elements and the author wonders if the artist was singing as he painted. It is a fairly quick work, which was nicely resolved. Glowing beauty of country.

Sunset scene with glowing plain, red hill and red foreground rocks, offset by bluish distant hills in shadow. Gleam of setting sun behind distant hills, but plain and rocks are brighter.

Gentle geometric diamond lines of dots infill back plain. Pale wash infills on front plain. Blob trees with fine black trunks lean to right.

The author hopes Ewald felt more of this glow in his later years.

REFERENCES TO EXTERNAL TEXTS

[1] Thomas Politzer, O.D., FCOVD, F.A.A.O., Implications of Acquired Monocular Vision (loss of one eye).