The founding of the watercolour movement was the culmination of the unique long term interactions between the mainly Western Arrernte people of the Ntaria area with the German Lutheran Mission community. Together they evolved into a relatively idiosyncratic isolated community over a period of more than fifty years after the original missionary arrival in 1877 of a small group with livestock.

The Original Missionaries

In 1877 the original Missionaries had settled on a special cattle lease in the most fertile country in central Australia in the broader area of the Finke River Valley between the scenic MacDonnell and James Ranges. The lease of the country of the people of the Ntaria area was, in keeping with the terra nullius attitude of the time granted by the colonial government of South Australia in Adelaide.

From the time of their arrival, the Missionaries gradually engaged with cautious locals, giving food and clothing in return for helping to teach them to speak Arrernte and help with livestock and for presence at religious lessons.

From the start, Missionary Pastor Kempe bridged the language gap by showing impressive coloured pictures to illustrate the ‘truth’ of their religion. As a priority the missionaries learned Arrernte with the help of local man Tjita (father of future evangelist Tjalkabota, also known as “Blind Moses”). The local Arrernte people, who enjoyed singing, then learned some Christian hymns translated into their own language – and so started the evolution to this particular discrete community.

John Strehlow, (son of TGS Ted Strehlow and grandson of Pastor Carl Strehlow and his wife Frieda), writes that in turn the Missionaries were being studied by the Arrernte, leading to closer interaction. Noticing the Missionaries’ fondness for birds during 1878 “several heathens” gave them some green parrots. All the white people were charmed. Dorothea Kempe took them in charge while Kempe and Schwarz played a tune on their flutes which the birds then imitated… [3]

Recognising the historical neglect of attention to the experiences of missionary wives, John Strehlow studied his grandmother Frieda’s diaries and wrote her biography. John Strehlow states that a problem in getting to know the Arrernte was that although they were not nomads they dwelled in various camps near permanent water and kept moving around.

Tjalkabota

In contrast to his father Tjita, who adhered to the traditional totemic religion, the young boy Tjalkabota (born most likely in 1872) had concerns about aspects of traditional religion especially periodic tribal massacres.

This was especially after the massacre of neighbours at Running Waters Irpmangkara in 1875, which included two of his playmates. (Moses biography, p242) His family group had deadly enemies on most sides and, as explained by Peter Latz, having no knowledge of anything better, young Tjalkabota could only assume that revenge was what life was all about. The situation changed with the arrival of Missionary Kempe and his group in 1875.

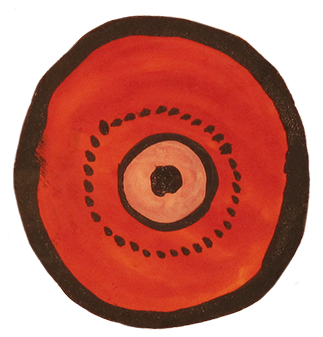

Tjalkabota accepted Christianity and chose Moses Tjalkabota as his baptismal name in 1890. He was forcibly initiated in 1892, an event that would have given him acceptance later among his traditional people. Tjalkabota grew up to be a famous evangelist. Inspired by Pastor Kempe, Tjalkabota constantly showed pictures to his listeners as he argued that they demonstrated the truth behind the bible stories. He said that he could show pictures of Christ and his crucifixion to demonstrate the truth, unlike the symbolic marks incised on the stone or wood tjurrunga, which was given to each young initiate with his individual design. [4]

The symbolic marks on the sacred tjurunga stone, Philip Jones explained, were part of a flexible vocabulary of symbols. [5] Ian McLean states that tjurungas are pieces of stone or wood that are engraved with pictographic records of the owners’ Dreaming stories or genealogy. They are the most secret sacred objects for the Arrernte and a few other groups in central Australia. [6] Philip Jones continued that the two most potent “objects” in Arrernte cultural life have been the sacred tjurunga and the landscape which embodies these. [7] [8]

Moses Tjalkabota was an engaging talker. He was very intelligent. He had a dignified presence both in manner and in his custom of dressing in white. Moses Tjalkabota was persuaded by Pastor Carl Strehlow, who took charge of the Mission in 1894, that the venereal diseases pervading and killing the local people could be controlled if partners were faithful to each other. Moses Tjalkabota sought to persuade locals to change from violence in both revenge killings and toward women.

In keeping with his traditional marriage arrangements made for him, Moses Tjalkabota married his promised bride, 15 year old Sofia in 1903. They had nine children. He was struck blind by measles in 1906. They coped with profound misfortune and sadness including the death of all of their children. Little is known of his wife Sofia who guided him steadfastly in his far ranging visits away from Ntaria over the area of influence of the Finke River Mission. When Carl Strehlow died tragically in 1922, Moses Tjalkabota filled the immediate void until Pastor F.W. Albrecht took charge in 1926.

A year or two before he died in 1954, Moses Tjalkabota dictated the story of his long life to missionary Pastor F.W. Albrecht. It was translated and published in 2002 by Paul Albrecht, son of F.W. Albrecht. Fortunately, Peter Latz, who was much closer to the Aboriginal world than his lay missionary parents, completed the biography by including explanations of aspects of Arrernte life that Moses Tjalkabota did not need to explain to Pastor Albrecht. Peter Latz knew Moses Tjalkabota personally when Peter was a child in Hermannsburg. Latz stated that as he was no longer a believer he felt able to be somewhat dispassionate about the lives of the Missionaries.

Hermannsburg Mission Society

The Missionaries were from the Hermannsburg Mission Society, which was founded by Pastor Ludwig Harms a charismatic preacher from Hermannsburg near Hamburg in Germany, in 1849.

After explorers Ernest Giles and William Gosse reported that they had found fertile country, “swarming with heathens”, in the very centre of Australia, Pastor Harms was impressed. Thus the Hermannsburg special cattle lease in central Australia was surveyed in 1876 and granted by a sympathetic government in colonial South Australia. This occurred many decades before other cattle stations took up leases and also before it was considered feasible for government activity to effectively reach northern areas of Australia.

By 1890, the missionaries were pessimistic about the survival of the Aborigines as a race, especially seeing the extent of pursuit of Aboriginal women by European men. [6] John Strehlow states that no official mention was made by anybody on the Horn Expedition that the white stockmen working at Hermannsburg and Glen Helen, and likewise those at Tempe Downs, were living with Arrernte or Loritja women as elsewhere, but that they must have been aware of it (around 1894). [9]

During 1889-91 the missionaries left Hermannsburg due to illness and school classes lapsed. The Mission was deserted until October 1894.

In May 1894 Baldwyn Spencer, biologist and photographer for the Horn Expedition (the first scientific expedition to central Australia), visited and submitted an adverse report on the lapsed Mission with the South Australian Government. In his ethnologist perspective Spencer was opposed to the influence of missions, which he considered were involved in the degeneration of traditional culture. [10]

In October 1894 Pastor Carl Strehlow, aged 22, arrived to revive the Mission, enthusiastically (if somewhat zealously at first). Over the next decade Strehlow organised construction of extensive new infrastructure and accommodation and provided for separate boys and girls dormitories and for the locking up of girls at night. Strehlow led a campaign against religious Arrernte traditions. [11] They actively persuaded converted Christians to cease their former religious ceremonies.

Chief Protector of Aborigines

After the Australian Commonwealth Government took responsibility for the Northern Territory from South Australia in 1911, Baldwyn Spencer was appointed Chief Protector of Aborigines.

In 1912 Spencer urged the Commonwealth to take over the Hermannsburg lease reporting inefficiency and unacceptable treatment of Aborigines, low standard of education and its policy of locking girls in dormitories. The Commonwealth withdrew its subsidy for rations between 1917-23, but did not take over the Mission. [12] Arguably, the Commonwealth at that stage lacked the practical capacity to take over the Mission.

Segregating girls and boys in dormitories

The policy of accommodating and segregating girls and boys in dormitories was said to enable better discipline and thus control of teaching. The policy of locking girls in dormitories at night was controversial. It may have partly reflected concern perceived from around 1890 about the viability of the Aboriginal race given the extent to which European men pursued young Aboriginal women.

However, according to John Strehlow it was because the youths and boys were ‘determined as ever to seduce the girls’. [13]

Men and Women

Strehlow developed a very close rapport with local men who in turn shared details of their religion and culture, the nature of which was excluded from women, and thus Carl’s wife Frieda. Frieda’s diaries reveal that her role as a wife of a missionary was unhappy and the major cause was her lack of rapport with Aboriginal women.

Aboriginal women appeared demoralised. They had lost their major organising role and responsibility in food gathering including that related to shifting of locations to camp near abundant food after rain, for example. The Mission provided sustenance in times of shortage or drought. [16] The women became sedentary and were thus sidelined from a purposeful role and their apathy in child rearing (according to Frieda Strehlow) perhaps reflected this. However, the men dominated ceremony albeit in the modified form as practised out of sight of the Missionaries.

Carl Strehlow died tragically on the tortuous journey south from Hermannsburg to seek medical attention in 1922. After a gap of four years when visiting pastors and the native evangelists led by Moses Tjalkabota ran religious activities, Pastor Friedrich Albrecht arrived and took charge in 1926.

Christianising

Christianising of the local people had entrenched to an extent that in 1928 the Aboriginal evangelists led by Moses Tjalkabota and Pastor Albrecht led a campaign against the traditional religion of the tjurunga in a ceremony at Manangananga Cave. [17] The tjurunga were de sanctified by being exposed to the view of the uninitiated plus women and children.

The unique Arrernte and Lutheran Mission community evolved within an effective governmental policy-free-zone, after the Australian Commonwealth Government relieved the state of South Australia from its responsibility for the Northern Territory in 1911 because of the latter’s lack of policy priority or capacity to govern for northern Australia.

Only ten years after the Federation of Australia, Commonwealth Government activity was limited at this stage. Financial power was weighted mainly with the States as the Commonwealth Government lacked substantive taxing powers beyond customs and excise. Until after the Second World War, general development of the remote Northern Territory was neglected.

During the devastating drought in central Australia from 1925, people could not depend on their own tribal groups’ countries for survival and came to the Mission area and outposts for sustenance. This accelerated the process of detribalisation which had begun in Carl Strehlow’s time with provision of some rations. Tribal identity until then was more rigidly tied to surviving in a tribe’s traditional country.

REFERENCES TO EXTERNAL TEXTS

[3] John Strehlow, The Tale of Frieda Keysser: Frieda Keysser and Carl Strehlow: an historical biography, p365 [4] Paul G E Albrecht, From Mission to Church 1877 – 2002 [5] Jane Hardy, JVS Megaw, M Ruth Megaw, The Heritage of Namatjira: The Watercolourists of Central Australia, p109 [6] Ian McLean, Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art, p78 [7] McLean, p112. [8] Sir Baldwin Spencer and FJ Gillen, The Arunta: a study of a stone age people, Ch VI pp99-134 [9] WC Hartwig PhD, quoted in The Heritage of Namatjira, p75 [10] Strehlow, p463 [11] McLean, p77 [12] The Heritage of Namatjira, p66 [13] The Heritage of Namatjira, pp80-82 [14] Strehlow, p817 [15] Barbara Henson, A Straight-out Man: FW Albrecht and Central Australian Aborigines, p247 [16] Henson, p247 [17] Strehlow, pp988-9 [18] Philip Jones in The Heritage of Namatjira, pp122-3.