1926 – 1989

Kaapa Mbitjana Tjampitjinpa was the major transitional artist between the watercolour landscape tradition of the Hermannsburg School and the Geoffrey Bardon initiated transformation of traditional Western Desert Aboriginal Art at Papunya from 1971.

From the late 1950s Kaapa Tjampitjinpa was based in Papunya, north-west of Hermannsburg, among people of several tribes and homelands. Kaapa was one of three former stockmen from Napperby cattle station, who were Anmatyerre and according to Geoffrey Bardon, the three were the most independent men at Papunya. Napperby people had escaped experience with missionaries and anthropologists. There were a few Western Arrernte people.

According to Ian McLean, three schools of art were practiced at Papunya. The best known, practiced by the Arrernte painted in the Namatjira watercolour style.

The bush Pintupi made traditional artefacts.

A third group of artists of whom Kaapa was the chief practitioner, were making hybrid wood carvings. Included in the third group were Kaapa’s Anmatyerr relatives from Napperby. Associated with the third group were ‘old men’ of senior ceremonial authority. [1] Other tribes at Papunya included Kukata, Ngalia, Wailbri, Loritja. (NT Census Papunya 1961, 1969)

After extensive study of the formation of the Papunya movement, Vivien Johnson dubbed the third group the ‘School of Kaapa’. [2] Both McLean and Johnson state that the Papunya painting movement emerged from the dynamic School of Kaapa. The other two Anmatyerr artists were Tim Leura and Clifford Possum.

As described below, Kaapa was painting in an artistic practice based on Aboriginal traditions before Bardon arrived in Papunya.

Kaapa was employed in the construction of the government settlement of Papunya. It was in Papunya that Albert Namatjira served his two month prison term in 1959 and where he created his last paintings before he died on 8 August 1959 in Alice Springs Hospital.

Kaapa was painting Hermannsburg School style watercolour scenes during the 1960s and to early 1971. Kaapa became the visionary founding leader of the transforming Western Desert art movement in a role in which he excelled.

Albert Namatjira’s fourth son Keith Namatjira lived at Papunya, at least during the early years of the Western Desert art movement. Although Keith opted to continue in the Hermannsburg style, in 1971 he paid homage both to Kaapa and a Papunya method of screening sacred symbols with dotting.

Joshua Ebatarinja, son of Walter and Cordula Ebatarinja, also lived at Papunya and started to paint in the Hermannsburg style in the mid-1960s. Joshua who died in 1973 continued in the Hermannsburg style. Both Keith and Joshua were raised in the Hermannsburg Mission culture, unlike the more traditional men who joined the new Western Desert art movement at Papunya.

Surviving pictorial landscapes by Kaapa (observed by the author) are on good quality supports, such as artists paperboard for watercolours and Fredrix canvas panels. It seems that there may have been some indirect or direct involvement through the Finke River Mission in the supply of good art materials, which Kaapa managed to obtain and adapt to watercolour painting. He had a reputation for being persuasive. Enos Namatjira also experimented with a similar type of canvas panel for at least one of his paintings created between 1960 and his death in 1966.

Kaapa in his way asserted his independence in the Government-dominated culture of Papunya. Although the FRM had a resident pastor in Papunya, the organisation and construction of Papunya and the often forced removal to the settlement of people, especially the Pintupi from far out west of Papunya was a Government initiative and activity.

An example of Kaapa’s watercolour paintings is Untitled, est. 1965-71 (watercolour on paperboard; 35 x 53 cm; Flinders University Art Museum 3076). [3] This was inspected by the author.

This may have been created in the Belt Range near Papunya and is in a Hermannsburg format. The tree trunks appear flat and more in silhouette than round. This is quite a fluent painting, indicating that the artist was sufficiently experienced to be at ease painting in watercolour ground washes on the paperboard, if not on the more absorbent canvas panel.

Perhaps Kaapa was guided by Keith to paint in watercolour as well as using lemon for back-lighting as demonstrated in Keith’s painting of 1971. [4] Kaapa named one of his sons Keith.

Kaapa created at least two paintings on canvas board but, in the paintings illustrated below, was not at ease painting smooth broad washes on the more absorbent support. These archetypal compositions are in similar country to that in Keith’s painting mentioned above.

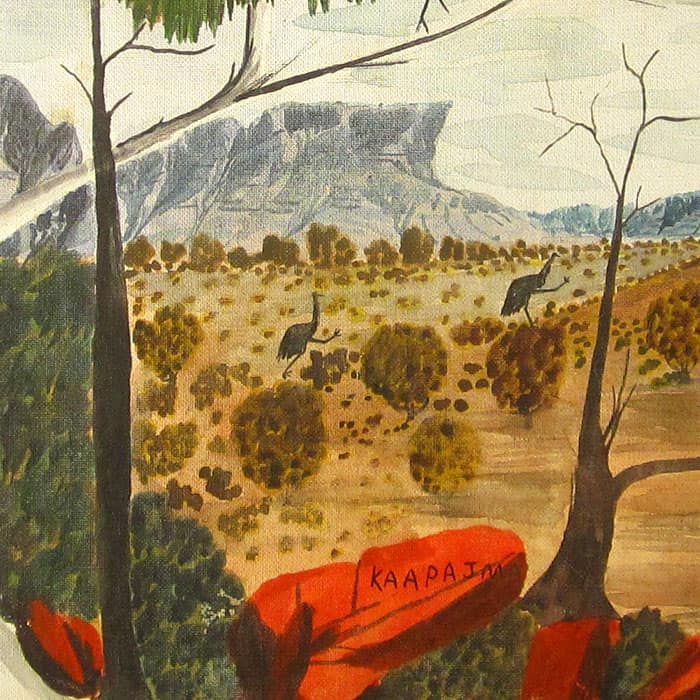

MacDonnell Ranges

Kaapa Mbitjana Tjampitjinpa

• • •

est. 1965-69

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas board or perhaps watercolour

40 x 50 cm irreg.

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-KTj-01

Hills with high rugged cliffs stand on a plain decorated with lines of dots for trees at the bases of the hills. The foreground includes verticals and red rocks to improve the structure of the composition. The device of the leafless small black tree continued in the transitional Papunya boards. There is no large Hermannsburg School type ghost gum or big tree.

Kaapa had somehow gained at least these two canvas boards, but was not at ease painting on them. He seemed unaware of methods of applying a coloured wash as a ground when he created this painting.

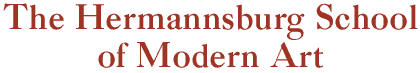

Emus on the plain, MacDonnell Ranges

Kaapa Mbitjana Tjampitjinpa

• • •

est. 1965-71

Synthetic paint on Fredrix Canvas Panel (cotton acrylic primed)

61 x 75.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-KTj-02

In pictorial terms Kaapa, the Emu Man, asserted his personal identity and tribal authority in the Emu Dreaming in the centre of this composition. This displays the artist’s light hearted personality and the playful emus some distance away on the plain are painted to be large enough to catch the eye of the viewer.

Kaapa, like his fellow Anmatyerr artists, was of the emu totem. This composition started as a Hermannsburg style archetypal scene and evolved with some excitement into a personal symbol of identity.

The artist was happy to portray his totem to non-Aboriginal viewers regardless of what the elders might think, suggesting an assertion of some independence from his elders.

A broad plain extends from behind the foreground to distant grey hills, as viewed through a wide gap. A grey wet season sky and schematic distant hills of bluish grey define the distant boundary. There is the end of a range with red cliffs on the left and a closer range of red cliff tops is on the right.

A bland mid ground horizontal area of the plain between the foot of the right side range to the foreground was then applied thinly in muted browns. Next applied were jaunty red rocks and low dark greenery to form the narrow foreground.

On the foreground a central ‘personal’ area was defined with a slender black bare tree on each side. A Hermannsburg School style of big white trunked tree was painted to the left of the left bare tree with its foliage and a long branch reaching over the centre area. Two emus skip prominently. Kaapa’s design device signature KAAPA JMA features on the jaunty red rock beneath the emus and between the slender black trees, completing the symmetry loved by Kaapa.

Kaapa emphasised his portrait area by painting the left black tree over the front of the extended branch of the Hermannsburg big tree. This portrait area is decorated with emphatic dotting to be read as trees or the surface of the plain. The small tree forms are backlit with yellow.

The area of the composition outside the portrait area is schematic, except for painterly devices which extend to the portrait, including the dotting at the base of the left range and the small trees extending across the plain on the right of the portrait area.

Luminosity and transparency did not seem important to Kaapa, although he painted bright red foreground rocks.

This is a delightful painting and the artist had become somewhat more at ease painting on the canvas board. He used the foreground to reinforce the verticals on the cliffs. Dotting was used for decorative infill on the left, but as part of his personal statement in the centre.

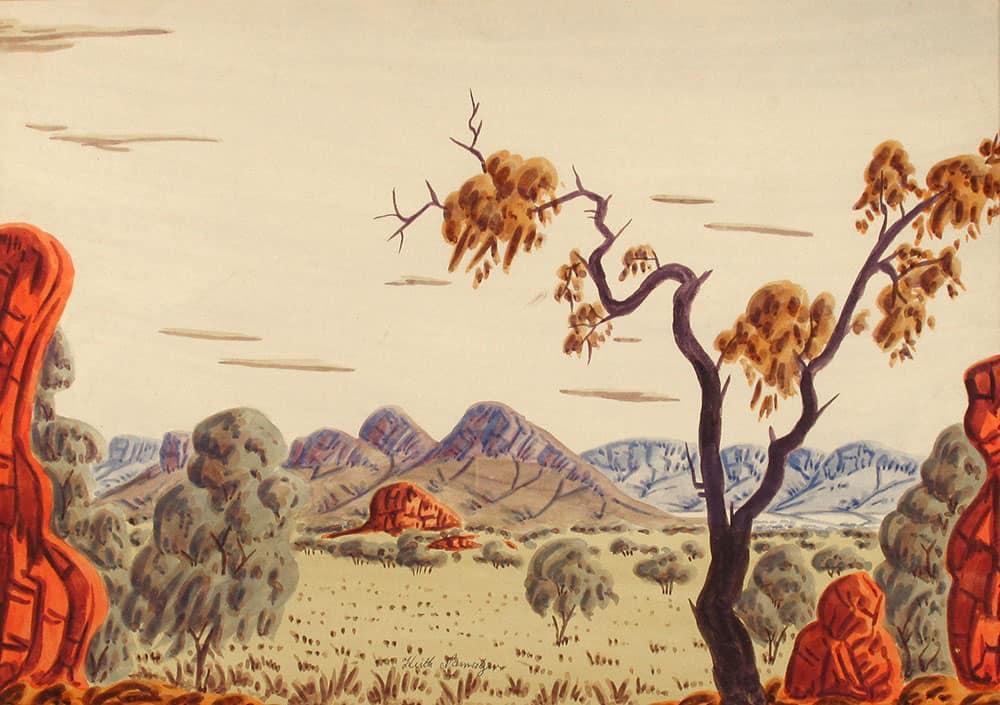

Kaapa’s device of bare black silhouette usually leafless tree forms continued in some of his early post-Bardon compositions and perhaps Keith Namatjira was paying homage to Kaapa in 1973-75 in one of his memory paintings in the Belt Range with Keith’s version of a black tree (below).

Central Australian GumTree

Keith Namatjira

• • •

1973-75

Watercolour on paper.

33.5 x 47.g cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-KthN-10

Keith Namatjira and Joshua Ebatarinja also lived and painted there. Kaapa likely met Albert and, being involved in art from his Napperby station life, would have been inspired by him.

Kaapa’s love of figuration as in the Namatjira watercolour style and in wood carvings of animals lingered and Geoffrey Bardon insisted that all artists cease white fella figuration.

A link between the Namatjira style and the School of Kaapa was observed by John Kean in Ceremonial Scene (Mikantji), 1971 (Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory; WAL 148; Luke Scholes (ed), Tjungunutja: from having come together, 2017) in a painting by Kaapa, shortly before contact with Bardon.

This painting on plywood was created by Kaapa starting with a Hermannsburg style lemon wash applied in obvious broad brush strokes. A black sinuous tree with foliage at near the left margin has a large goanna alongside: the restricted symbolic area has been cropped from the illustration. Kean considers that the painting may be a missing link between the Hermannsburg School and the School of Kaapa. From this painting six more were created and entered in the Caltex Northern Territory Art award. One as illustrated by Ian McLean [5] could have been prepared as another part of the sequence, having been given a primary wash of lemon, with a similar border around the edge.

Vivien Johnson concluded that Kaapa was still working independently of Bardon when six paintings delivered on behalf of Kaapa by Jack Cooke, District Welfare Officer, in winter 1971 to Alice Springs, were in a sense ‘some of the last to be painted in the pre-Bardon style, that is, before Bardon’s first period in Papunya from ‘immediately before the completion of the school murals in June 1971 to December 1971’ [6]

Cooke entered six of Kaapa’s paintings in the Caltex/Northern Territory Art Award. Until this time, the Art Award had typically displayed conservative white territory art. It was announced on 27 August 1971 that Kaapa won the prize for Gulgardi. [7] Therefore Gulgardi was the product of an artistic practice based upon Aboriginal traditions which existed in Papunya prior to and independently of the painting group that gathered around Geoffrey Bardon.

Geoffrey Bardon left Papunya in July 1972 following a mental breakdown during political machinations over the management of the art cooperative. In November the artists legally incorporated their cooperative into a company called Papunya Tula Artists, with Kaapa as its first chairman. [8]

The energetic early development of traditional Aboriginal art in the new form was described by Terry Smith as standing ‘in stark contrast to the complex crisis of painting in recent western art.’ [9] Western contemporary art had effectively lost momentum in Australia and internationally.

In considering Kaapa’s transition to lead the Western Desert movement it is relevant to note that Wenten Rubuntja from the contrasting ‘city’ culture of Alice Springs started painting in his version of two ways (Hermannsburg and traditional) in the mid-1970s, after painting in Hermannsburg style watercolour from after the death of Albert Namatjira. An Arrernte man who grew up free of the rigours of both traditional and mission influence, Wenten became a major leader of the land rights movement in 1976. He asserted that the traditional way of painting was akin to ‘the law’ and the Hermannsburg style as ‘the song’. Wenten became Chairman of the Central Land Council in August 1976.

REFERENCES TO EXTERNAL TEXTS

[1] Ian McLean, Rattling Spears: A History of Indigenous Australian Art, p126 [2] Vivien Johnson, Once upon a time in Papunya, p27-28 [3] Jane Hardy, J V S Megaw and M Ruth Megaw eds. The Heritage of Namatjira: The Watercolourists of Central Australia, p19 Illustrated in black and white with date of ‘c 1980 Kaapa Mbitjana Tjampitjinpa’ [4] Geoffrey Bardon and James Bardon, Papunya: A place made after the story; the beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement, no. 56 on p137 [5] Bardon, p xxii [6] McLean – Figure 60 on p131 [7] Johnson, p17 [8] McLean, p133 [9] Bernard Smith with Terry Smith, Australian Painting 1788-1990, p495