1914 – 1973

The three Pareroultja brothers – Edwin, Otto and Reuben – made a huge contribution to the quality and distinctiveness of the Hermannsburg School. The oldest of the Pareroultja brothers, Otto, started to paint in 1946 when aged 22 years, after Enos Namatjira and Walter Ebatarinja had started to paint seriously. Edwin had been painting for a couple of years, when Rex Battarbee spoke to Edwin and said that it was a pity that Otto and Reuben were not doing more work.

Rex stated “At this time [late 1945] they were not doing very much, (although they had started to experiment before Edwin started painting seriously), probably because of lack of encouragement and because they did not know if they were on the right lines in trying to do something according to their own outlook.” Otto had struggled with drawing from around 1940.

In 1946 Edwin Pareroultja seems to have actively guided both of his brothers: first Otto and then Reuben. Otto began to paint seriously in 1946, after starting 1945.

Otto Pareroultja portrayed country that was vibrant and rhythmic. Otto’s paintings exude a high sense otherness, the other world of his tribal relationship to his totemic countries. The sometimes animate looking trees were marked to suggest totems with totemic-like striped markings. Any urge to describe them as ‘anthropomorphic’ is resisted as they may not be meant to attribute human qualities to the trees, but possibly some non-human spirit or ancestor.

As observed by Ian Burn and Ann Stephen in Heritage of Namatjira [1]: ‘In Aboriginal terms, the landscape is not mute, nor other; the history of the land embodies its cultural transformation, one through which Aborigines regard the landscape as an objectification of themselves’. Catherine H Berndt and Ronald M Berndt in Aboriginal Australians, refer to the spiritual essence of the country as the active ingredient of life, while the country is not usually referred to as taking the initiative, such as in starting bushfires. [2]

Sometimes attitudes emitted in his paintings ranged from tranquillity and delight to drama and anger. On at least one occasion he portrayed fierce conflict between elements of the totemic topography. He engaged pictorially with his audience by using expressive trees, hills and cliffs ‘to mime’ events theatrically. As he gained confidence, rhythm was employed with increasing dramatic effect.

Otto’s rhythmic approach was an action process no doubt borne from his experiences of song and dance. He was a baptised Christian, who also celebrated his traditional culture. Significantly, his family were known for their diffidence toward the Mission. [3] Consciously Aboriginal, he avoided using symbols unavailable to those ‘who were not in the know’. Otto was a founder and master painter of the Hermannsburg School.

Rhythm came first and intense colour came later. As he gained confidence, rhythm was employed with increasing dramatic affect to engage with his audience. First, he rounded geometric patterns to give vibrancy to rocks and hills. Second, he evolved a patterning style of rhythmic rounded marks with curved tails which enabled him to portray parts of totemic hill structures as pulsating (like a beating heart).

Otto seemed to invite his audience to consider whether the animated trees are participants or observers in the stories implied in the paintings. Likewise the viewer may consider elements of the topographic landscape as participants or observers or as features making up a scene. Otto was about engagement and thus embraced his audience.

Most of Otto’s paintings do not indicate the location in their titles, nor any helpful inscriptions about locations. The locations for his paintings included actual and archetypal scenes of the wide area of the Finke River Mission, including Haasts Bluff and Areyonga to the west of Hermannsburg, Palm Valley to the south, Glen Helen and Ormiston to the north and eastward including to Jay Creek and Heavitree Gap at Alice Springs. Many, being based on legends, would have been ‘memory’ paintings, a concept so important in Aboriginal tradition.

Otto married Laurel Kekainan, a Loritja woman, and as at 1957 they had three children, including future artist Trevor. Otto and Laurel were in Alice Springs when Trevor was born in 1941. Otto was Western Arrernte, Subsection (Skin) Kngwarreye.

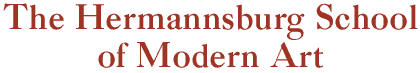

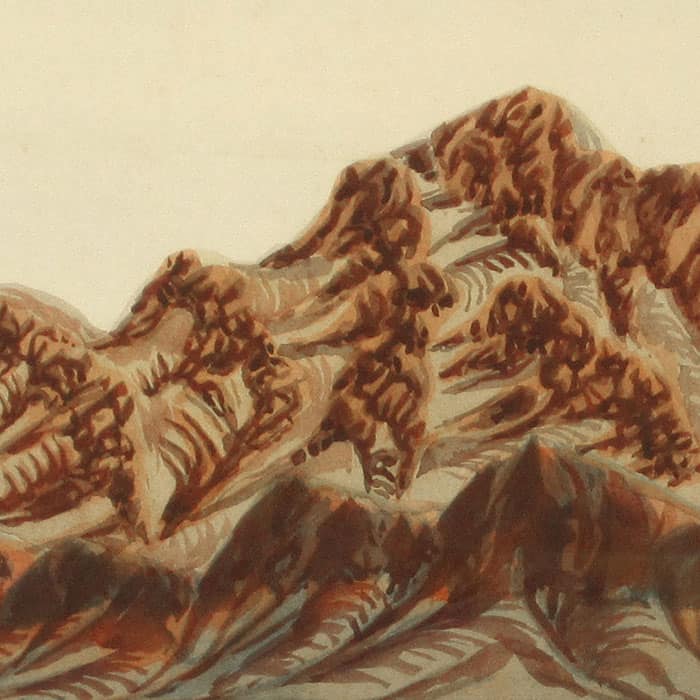

Mt Sonder

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

est. late 1945

Watercolour on paper

24.5 x 33 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-15

This early tentative painting shows influence of watching his brother, Edwin, apply broad fields of clear colour early in the painting process. The tree foliage is backlit with lemon and pale washes were applied early before the rhythmic shapes were added. Otto has applied curved parallels on the mid ground hill, the distant hills and the tree trunks. The trees are somewhat animate. The trunks have tentative marks on them. This pale painting was created before the direct influence of Rex Battarbee who encouraged Otto to use more intense colour.

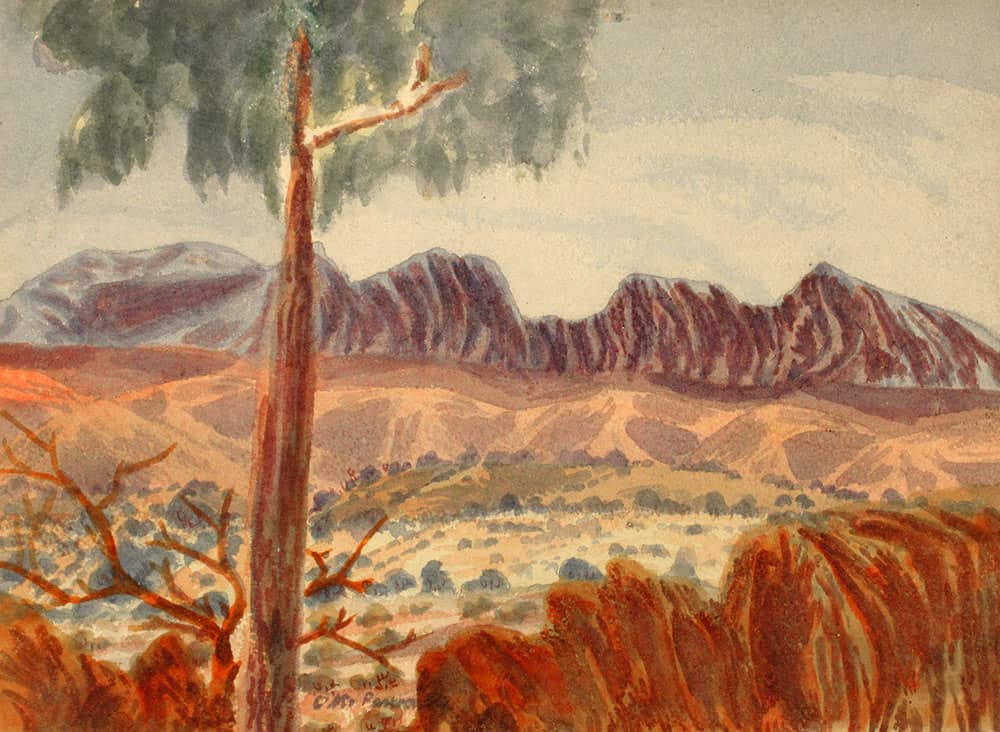

Blue Mountains

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

est. early 1946

Watercolour on paper

26 x 37 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-16

This was created soon after The Hill, est early 1946. It shows a continuation of the separated colour fields upon which Otto’s painted markings became a more concerted exploration of rhythmic patterning, which he pursued through his career. Colour became more intense in this painting as he developed confidence. The solo tree is a firm presence.

The rhythmic parallels on the blue mountains are repeated in the right foreground. Infill on plain is of curved lines and lines of dots and parallels.

In early 1946 a significant collaborative painting was created by Otto and Edwin: PAREROULTJA: Near Glen Helen, Hermannsburg est early 1946 watercolour on paper signed: Pareroultja. It is in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia (NGA). NGA 873 94. 1265. This ‘teaching painting’ appears to be mainly by Otto, under guidance from Edwin as his teacher with horizontals of colour fields to suggest distance/perspective. The curving tree appears to have been added by Edwin as a device to frame the scene and unite the static horizontal areas. Note it is signed ‘Pareroultja’, that is without a first name. Verso: ‘Alailtama MacDonnell Ranges’. Otto was beginning to experiment with rhythmic geometric stylisation.

Wall of Amphitheatre, James Range

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

est Sep/Oct 1946

Watercolour on paper

25 x 35 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-23

This is an important breakthrough painting, possibly created or commenced on site in Palm Valley. The patterning emerged in the late stage of this unassuming painting as Otto was inspired to stylise rhythmic marks and thus impart vigour into his creation.

Having painted the amphitheatre wall and rounded cliff-tops, and then the foreground blue foliaged trees, Otto enlivened the central mid ground with intense magenta blobs marks over lemon and green tentative paint-work.

To these blob marks he added rhythmic ‘tail-like’ curved lines to gently complement the parallel curving lines on the amphitheatre walls. The painting was resolved by horizontal magenta lines, appearing to continue these lines near the right edge. The blob/tail device complemented the cliff top patterning.

In later paintings Otto gradually developed this blob/tail device (of the lower centre) to impart rhythm in describing hills as in Central Australian Landscape and then the pulsating energy in The Birds of Central Australia on this page.

Note – this composition is outlined on the hill in fine 6B pencil, which has smudged at left. The sky is pale blue with no recession and the hills are magenta and ultramarine. Lemon is involved in the ultramarine blobs and there is a hint of yellow/pale orange on the right hill top.

In 1950 Otto started producing paintings with an animated tree, usually as the dominant part of the composition and with totemic type markings on the trunk. The trees were normally gum trees. Otto was the only painter to do a series portraying a tree or pair of trees as the dominant actor or actors in dramatic situations.

Note – Ewald Namatjira did a couple of large paintings with a central foreground tree but Ewald’s trees were present in a somewhat varied role of dominant observers. Otto’s trees in this series were actors and parts of the landscape were participants. Richard Moketarinja did a number of vertical scenes with central foreground trees. Richard also did horizontal compositions with central foreground trees.

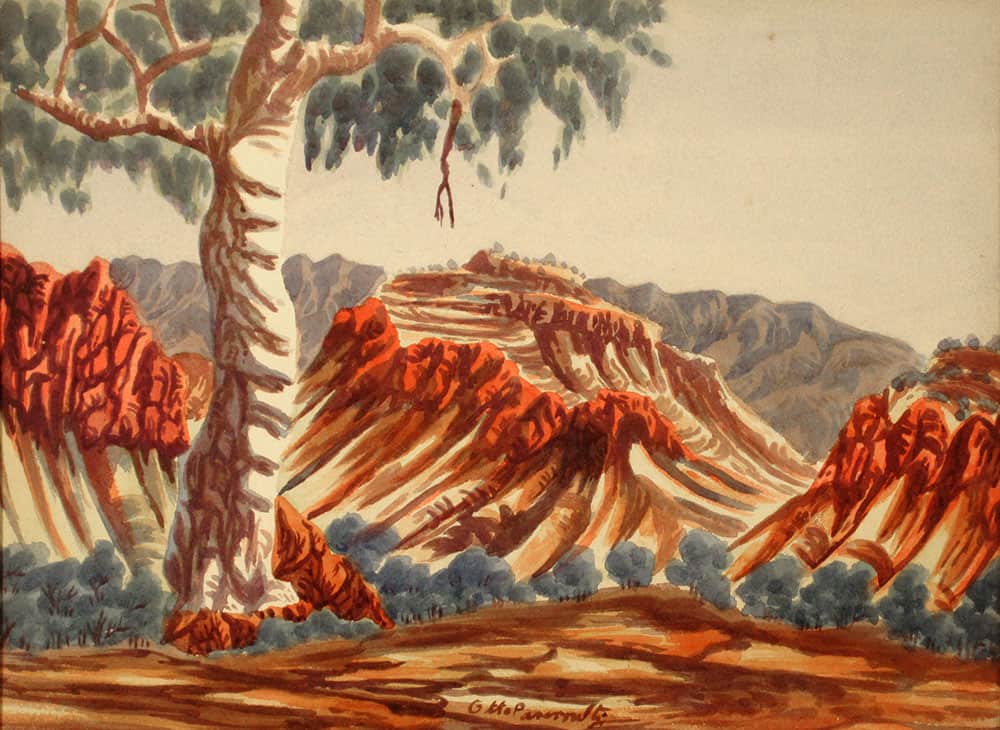

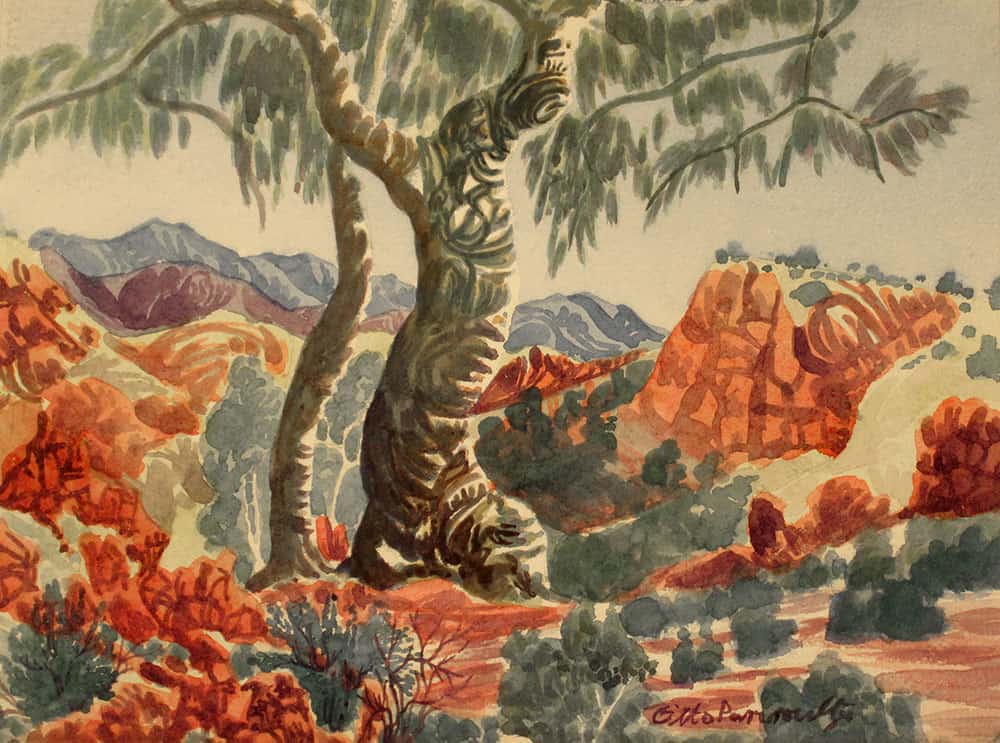

Ghost Gum, MacDonnell Ranges

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

1950

Watercolour on paper

27 x 37.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-04

The totemic tree beholds the three hills, each with their animate red cliff tops. It stands near the left hill but appears to face the centre and right two hills. The hills may portray spiritual beings which the Arrernte people believe were involved in myths.

In this composition the totemic tree stands on high ground above a central hill and a second hill to its right, both with animate red cliff tops which are suggestive of faces which are similar or related to each other; and a hill at left near the tree with different looking cliff tops and with cliffs that slope down beneath the tree.

The tree stands on a small rock structure, which is patterned like that of the left cliff. The left side of the tree has a similar pattern. The left branch is extended over the left cliff and the right branch is extended over the central hill, suggesting that the tree is engaging with the hills. The trunk continues above the top of the composition.

The curved parallels on the totemic tree trunk’s right side are at one with the hills on the tree’s sunlit side, while the shaded side at left has a complex pattern like the nature based cliff at the left of the painting. Otto’s pattern system of blob marks with pointy curved tails on the central hill invigorates this painting in a further stage from nature based patterning.

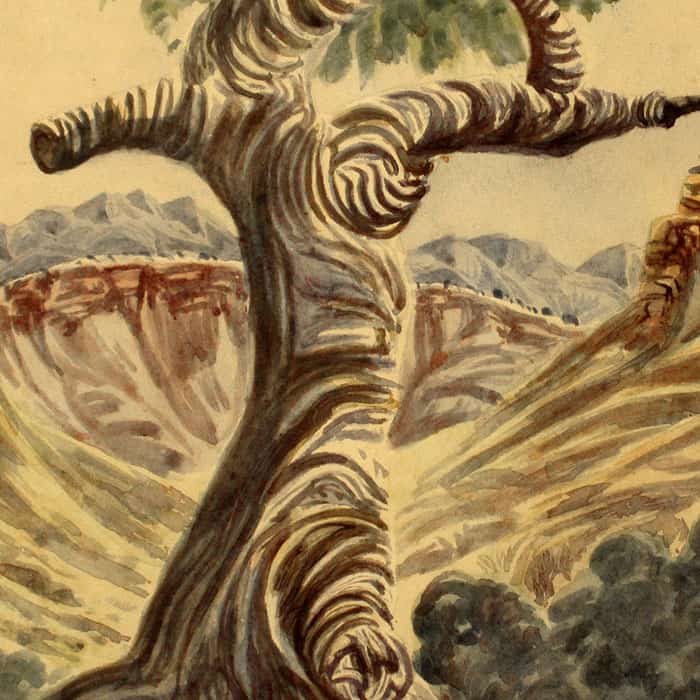

The gnarled gum (totemic tree)

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

1952

Watercolour on paper

28.5 x 36.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-05

This scene is somewhat confronting. Here, an angry tree dominates the landscape vigorously. The tree is wounded and mostly dead, but is depicted as though in defiant or combative movement. The composition is clearly about conflict and the tree and the cliffs at right are the protagonists.

The tree may have a head between upraised arms. Facing to the right and slightly towards the viewer, its left arm ends in dead branches, while the right has lost its branches above the ‘elbow’.

The trunk continues up above, indicating more growth above. The tree is not winning. The cliffs on the right side are sharply defined as involved in conflict, while the cliffs at left are neutral and in tune with the rest of the country. This is a familiar story to the artist.

The painting involves a lemon under wash on each side of the mid ground; curved parallel grey brush strokes 3mm wide; nature based patterning on each side cliff top. A dome curved hill behind the tree adds equivalence to the shape of the valley. Lemon yellow increases the sense that the cliffs seem to recoil away from the beast. Lemon is thus used by Otto to convey emotion. Beyond the recoiling landscape in the far distance are harmonious blue patterned peaks of a range in the outside world. There are three subtle colour fields, which echo the influence of the artist’s brother, Edwin.

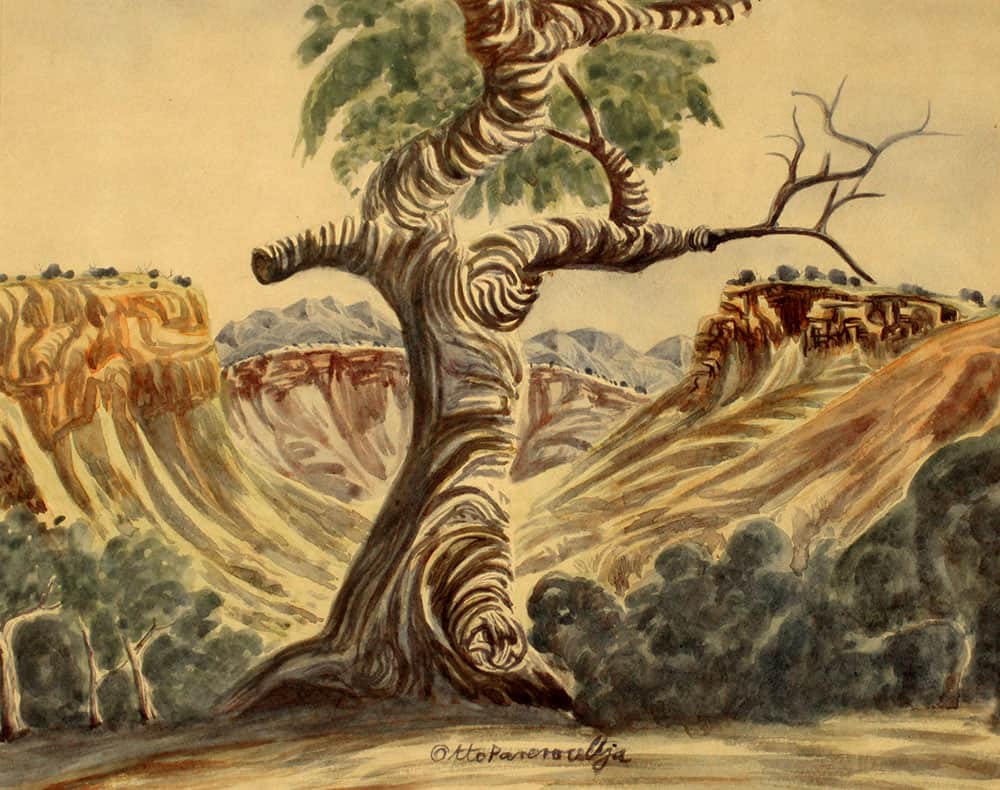

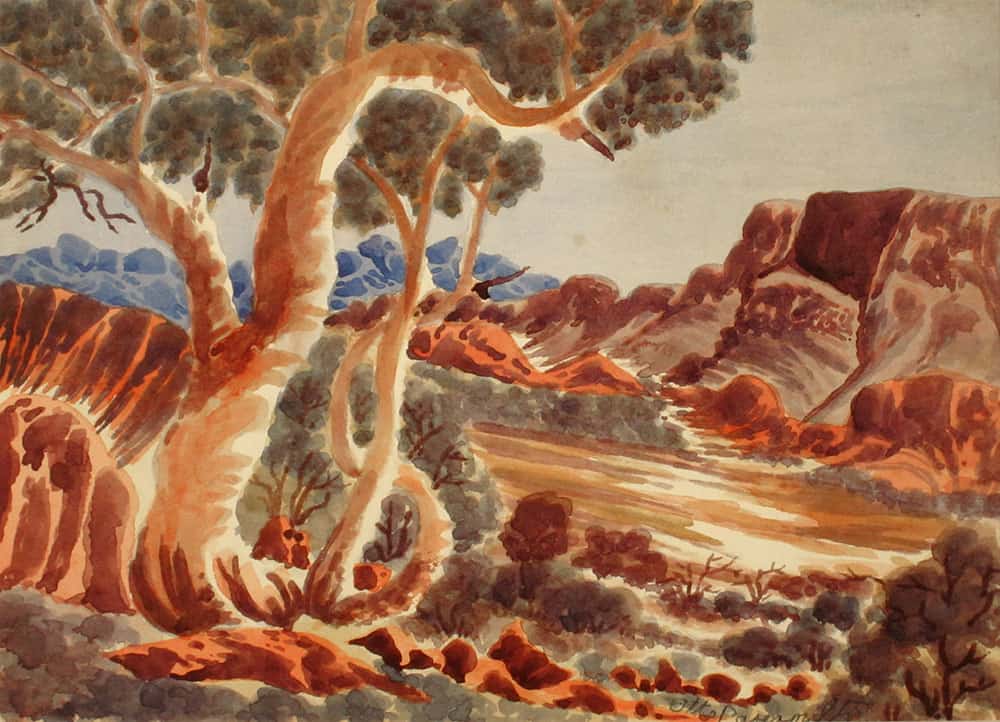

Near Mt Hermannsburg (totemic tree)

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

1954

Watercolour on paper

28 x 38.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-01

This composition portrays an old tree complete with black and white traditional markings on its trunk in front of a young tree, which has simple markings. The pair of trees may be euphemisms for a tribal elder leading or controlling a young initiate. As though in gentle movement, they stand on high in the hills, which appear to be vibrating with rhythm. The symbols on the trunk include concentric circles.

In the late 1950s Otto moved the central tree to side of centre: it remained the dominant ‘presence’ in the country, being more than an aesthetic device.

Totemic tree

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

est. 1955-59

Watercolour on paper

35.5 x 52.75 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-02

This is a scene of contentment and equilibrium. Although the animate tree frames the scene, it is very much part of the landscape and has aged into the status of a wizened and heroic elder. The ancient cliffs at right have face-like patterns.

The scene slopes gently down to the right and includes natural rock patterning and parallels. The geometrics of distant hills are based on natural shapes. Cliff top natural patterning is developing into blob marks with curved tails on right mid ground hill and red rocks beneath hill.

Around 1959 Otto created several paintings with important totemic and animated trees in principle roles, usually left of centre. An example is Twisted Gums pictured below.

Twisted Gums

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

est. 1960-69

Watercolour on paperboard

24 x 33 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-08

An elaborate tree twists and curves above a treeless slope down toward a range of inconspicuously painted greyed mid-ground hills. The tree stands amid red rocky outcrops, small red rocks, blob ground cover with small blob trees behind. Two young trees grow from its root base, one being fairly straight and the other is twisting and curving. Although the horizon appears horizontal, the steepness of the slope appears to be exaggerated.

The composition is sharpened by ultramarine two tone stylised rounded geometric distant hills. There are no colour fields. Straight and curved parallels and blob marks are important aesthetic devices.

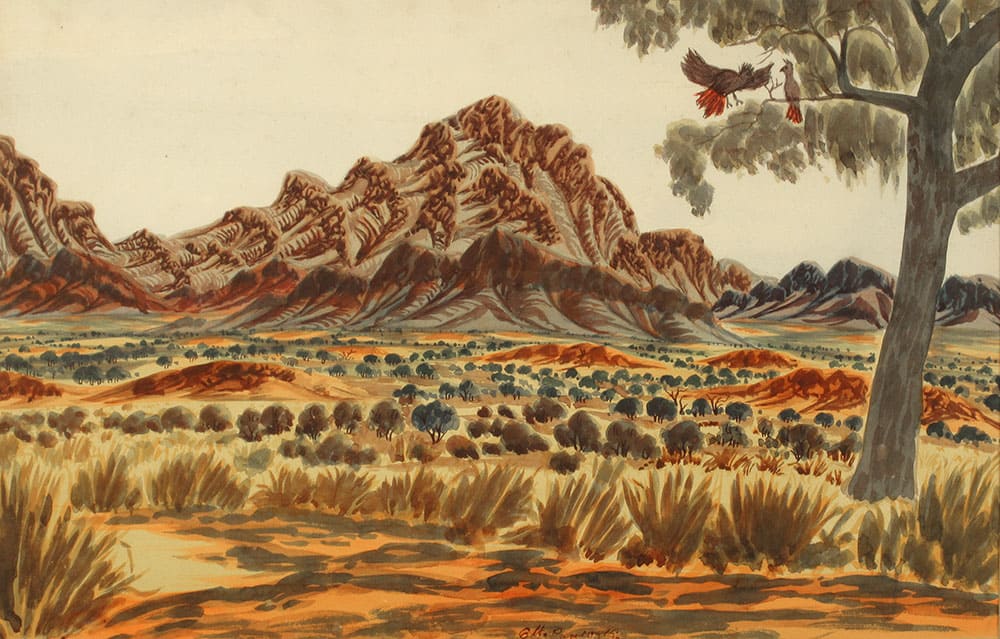

The Birds of Central Australia

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

est. 1960-69

Watercolour on paperboard

34 x 53.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-06

The central mountain appears to pulsate like a heart pumping energy into this vibrant scene. Otherwise, the scene appears still, apart from the cockatoos. The tree serves as a gestural device in tilting away from the vibrant hill. The glowing yellow plain has trees and important looking low red hills. The red ground of the viewpoint glimpsed in the foreground may be from the edge of another of the low red hills. Significant foothills surround the totemic hill. The inclusion of the black cockatoos may have been a playful gesture to complete this joyful portrayal of his country.

Otto’s patterning of blob marks with curved tails has culminated in this composition to portray a mountain that seems to be seething with life.

The finely drawn background hill is most important. Fine line work describes the red mounds and similar red paint describes the foreground viewpoint. From the red foreground to near the foothills, the plain glows with yellow. The birds’ bodies are in same blue as the big hill in front of the organic mountain. Tall grass dividing the red foreground and yellow plain is like a screen and may invite an appropriate approach for a visitor to enter the space. The mountain is surrounded by foothills.

There is a horizontal diamond pattern in front and behind the blue central hill, which stands in front of the background hill.

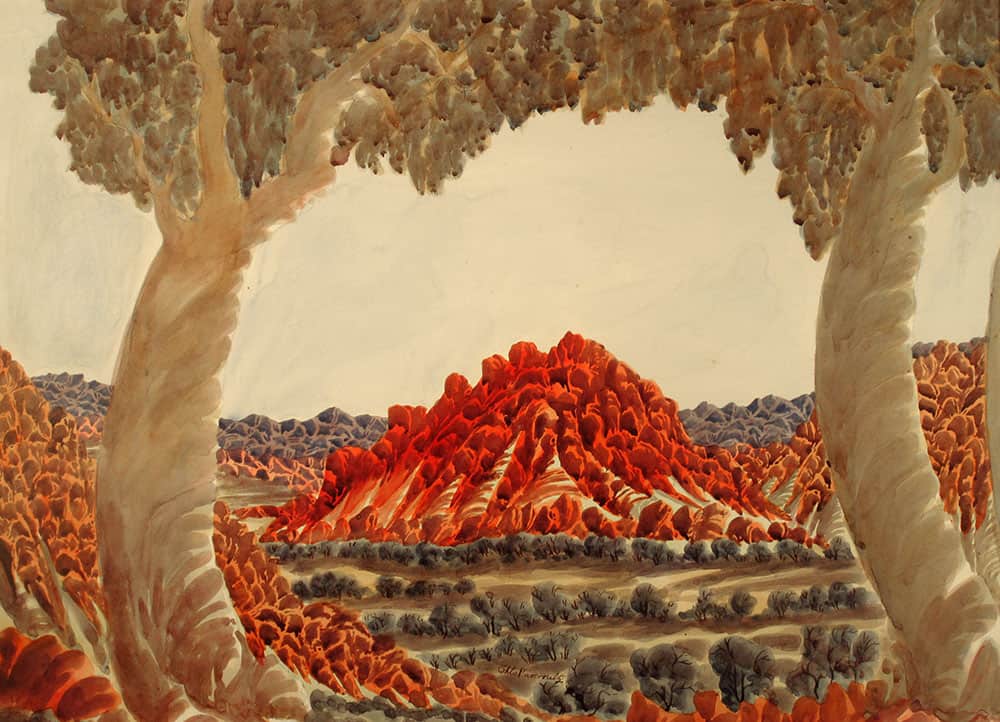

Twin Giants

Otto Pareroultja

• • •

est. 1967-72

Watercolour on paperboard

52 x 71.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-OPar-14

Calm guardian-like giant trees frame the view of the vibrant hill. The vibrancy of the rocky hilltop relaxes somewhat on its lower slopes of curving yellow bases above the more relaxed flat plain, which has lines of small trees. Three rhythms are involved in this song: the staccato of the rounded geometric patterning on the hills, the moderato of the lower slopes and the tree trunks and the legato of the sky and plain. The hill seems screened by low row of red rocks and rows of tree blobs.

Otto Pareroultja became a major Australian artist and surpassed his brothers in establishing a prolific career. Otto was proudly and consciously Aboriginal. With some familiarity of the sacred stories, he found a way to dramatise his totemic origins and his relationship to the country of which he was part: he did so without using secret traditional symbols. He did not reveal what the country meant but he did much more than describe how it appeared. Through his lens of interpretation he staged mythical dramas for his audience.

REFERENCES TO EXTERNAL TEXTS

[1] Jane Hardy, J V S Megaw and M Ruth Megaw eds., The Heritage of Namatjira: The Watercolourists of Central Australia, p272 [2] Catherine H Berndt and Ronald M Berndt, Aboriginal Australians, p16 [3] Diane Austin-Broos, Arrernte Present, Arrernte Past: Invasion, Violence, and Imagination in Indigenous Central Australia, p42