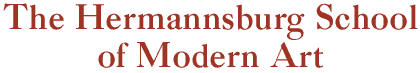

Observations from the Activity Chart of the stages of The Hermannsburg School

The chart shows each artist in order of starting to paint seriously in watercolour landscape. It omits wooden souvenir artefacts or sporadic drawing or painting attempts before starting to paint with some regularity.

The start and end dates on the chart are the author’s estimates derived from her study of the paintings in her collection and other collections available to her, and her knowledge of the artists’ lives. Obviously therefore, these dates must be understood to be approximate.

1930s

The chart starts with the pioneer and founder Albert Namatjira, who started to paint in 1936 in a luminous albeit naive style aiming to be true to nature, as shown by Rex Battarbee.

1940s

By 1943 when Edwin Pareroultja started painting Albert’s paintings had become quite detailed.

Next after Albert Namatjira are the group of eleven other founders of the Hermannsburg School who started to paint seriously during the period 1943-47 at Hermannsburg.

The first of the other founders to start painting seriously was Edwin Pareroultja in 1943, when he simplified and adopted Albert’s broad fields of colour, but intensified colour and minimised detail.

Enos Namatjira and Walter Ebatarinja started in 1945. Enos adapted design from narrow souvenir artefacts, such as boomerangs, with animals in action, changing to portray hilly ranges in apparent movement in relation to the flat and still plains. Using pale colours to start with, Walter built on Albert’s adherence to nature and Edwin’s colour fields. As he gained confidence Walter minimised detail and built his own system to enhance impact. He included simple markings of traditional origin.

Otto Pareroultja and his brother Reuben, Oscar Namatjira, and Henoch Raberaba started in 1946. After starting with pale colours applied rhythmically, Otto explored portraying drama and vibrancy in the topography.

Reuben combined Edwin’s colour fields with Otto’s rhythm to build a subtle delicacy of stylisation which exceeded that of most artists. Oscar was inspired first by his father Albert, then by Edwin and Otto to develop his own rhythmic spaced trees.

Henoch built on Albert and Edwin’s style to work out his own system of curved hill bases beneath rocky cliffs in which parallels were important.

The final four founders started in 1947, namely Richard Moketarinja, Ewald Namatjira, Adolf and Gerhard Inkamala. Richard built on parallels, used dots as infill and decoration, and explored aspects of traditional aerial and upright European pictorial perspective.

Ewald, then aged 17 years, had managed to avoid disciplined Mission schooling. He was guided by his varying emotions and sensitivities. Ewald spent much of his childhood in painting camps with his father Albert.

Adolf Inkamala started soft and detailed early work of rounded hills of a major valley out west of Hermannsburg. Gerhard Inkamala completed an early teaching painting started by Albert, in his naive patchwork looking style. Both Adolf and Gerhard emphasised steadfast trees.

From 1949 the circle of participation broadened to include more relatives: Kenneth Entata, Claude Pannka, Lindsay Imbarndarinja, Cordula Ebatarinja, Benjamin Landara, Herbert Raberaba, and Clifford Inkamala by 1955. The author describes this as the consolidation period.

1950s

The rate of new artists joining in declined after 1951, before a resurgence when twelve more started in 1958, 1959 and 1960, following the drama of Albert Namatjira’s trial, imprisonment and death on 8 August 1959. The author describes this as the resurgence period.

1960s

The 1960s was the busiest period with the highest number of artists painting seriously and at least eight more tried their hands at painting the occasional picture. Most of the founders were continuing in the 1960s and some of these were regenerating their styles as their attitudes to their world evolved.

1970s

From 1972 to 1977 the number tapered down to 10 who were painting and by 1981 only four were painting seriously.

The School produced many fine artists. Because the author is unfamiliar with the interpersonal dynamics of the group she is cautious in trying to classify some as leaders. However a few may be considered ‘masters’ of the Hermannsburg School: Albert Namatjira of course, Enos Namatjira, Walter Ebatarinja, Otto Pareroultja, Richard Moketarinja, Ewald Namatjira, Herbert Raberaba, Keith Namatjira and Wenten Rubuntja.

The right side of the activity chart looks frayed as the artists aged, died, or assumed other activities. Four artists stopped in the year of their death. Five stopped painting within one year before dying, including Keith Namatjira and Joshua Ebatarinja. Four stopped a few years before dying.

Sadly, many talented artists died young including Enos Namatjira at 46 years, Adolf Inkamala (45), Claude Pannka (44), Lindsay Imbarndarinja (about 40), Keith Namatjira (39), Maurice Namatjira (40), Gabriel Namatjira (27), Athanasius Renkaraka (44), Joshua Ebatarinja (32), Lindberg Inkamala (38), Trevor Pareroultja (42), Jillian Namatjira (42).

Establishing the date of creation

A major research task was to estimate the time of creation of each painting. After evaluation of all paintings, an evidence-based picture of the period of activity of each artist and the development of the movement was charted.

The artists did not inscribe the dates on which they created paintings. Although Rex Battarbee inscribed the year of creation beside his name on each of his own paintings, none of the Arrernte artists followed his example.

However, as part of the government policy of protection (and control) of Aboriginal people, artists needed permission to sell paintings. The Native Affairs Branch (of Department of Territories) Stamp of Authority on the reverse of the paintings included the date of authorisation.

For the purpose of research, the author has assumed that authority would probably be sought within a couple of months or so of a painting trip. Paintings bearing the stamp were generally expected to sell at higher prices than those without.

As many paintings do not bear the stamp, the artist may have sold the paintings independently in Alice Springs. Indeed some artists preferred to be independent and to sell directly, especially if they were camped near Alice Springs.

Paintings on paper were often glued to a cardboard backing during the framing process, obscuring any stamps or other inscriptions, such as a location details. The author has carefully removed such backings, while preserving the integrity of the paper and painting, to access information on the reverse side.

A small number came with evidence of an actual year or perhaps a more specific date.

The study of each artist’s development was enabled through examination of the large number of paintings in the author’s and public collections. Some paintings of ordinary quality were purchased if there was a specific plausible date provenance or if it provided a datum point for an artist producing a sequence of difficult-to-date paintings.

Abbreviations: In catalogue descriptions the term circa (Latin for ‘around’), means anything from within two to ten years. The abbreviated term est, (short for ‘estimated’) is used by the author to mean it is an estimate.