1915 – 1968

Walter Ebatarinja asserted his personal independence and tribal identity through his painting career from the early 1950s. By choice, Walter was initially taught by Albert Namatjira, rather than by Rex Battarbee. Walter created paintings, which maximised their impact by abstracting rock patterns and minimising detail. He produced romantic fantasies by exaggerating qualities such as tonal contrasts, surface smoothness and colour luminosity. He sometimes included tribal tjurunga markings with nature-based patterns in rocky outcrops and cliff tops. Walter Ebatarinja was a founder and master of the Hermannsburg School.

The Mission encouraged painting as a men’s activity. However, with her husband’s support, Walter’s wife Cordula became the first Arrernte woman to paint seriously from 1951. Cordula continued her painting career after Walter died.

Walter obliged Albert to teach him to paint in 1945, having asked Rex to give him tuition at about the same time. [1] According to Rex Battarbee, Walter Ebatarinja’s father was the headman of the Hermannsburg group of the Arrernte tribe. Walter was Western Arrernte. The Ebatarinjas were a prominent mission family. Walter along with his male siblings played at least in modest part the role of traditionalists. [2] Walter’s mother Ruth was half Aboriginal. In traditional terms Walter’s father was senior to Albert’s father who had no authority from a tribal point of view at Hermannsburg. Thus, when Albert became a successful artist he was obliged to help Walter to learn. [3]

Albert’s guidance to Walter was based on the stage Albert had evolved to in his painting in 1945 in which his emphasis then was on how the scene appeared. Albert’s early paintings in the 1930s started with a horizontal bands approach and very pale colour fields.

Walter steadily developed an individual style as he progressed in his career. Walter was a decisive and individual painter who developed his own direction, while building on aspects of other artists’ work, especially Albert Namatjira and Edwin Pareroultja. Walter absorbed Albert’s adherence to nature and Edwin’s primary colour fields into his own system in which traditional markings were important. Walter used aspects of traditional markings including the wavy lines sometimes found on the sacred tjurrunga, along with dots and parallels to simplify and achieve considerable drama. Walter also employed the grainy texture of the paper sensitively in his painterly style.

Walter seems to have been personally assertive. Walter and his wife Cordula were prepared to upset the (Mission and Northern Territory Administration) Aranda Arts Council system of attempted regulation of marketing and payments to Aboriginal artists in following their careers with some independence. Rex Battarbee and his wife Bernice had key roles in this important and challenging activity after their marriage in September 1950, when they established the Tmara Mara gallery in their home in Alice Springs.

Rex Battarbee stated in his 1971 book Modern Aboriginal Paintings that ‘Walter painted for a number of years with good technique and much ability, though perhaps without as much sincerity as Albert.’ Battarbee seemed reticent about Walter and included only one very early painting of 1945 in this book when he could have included a later example.

Members of the talented Ebatarinja family developed their own individual styles. Walter and Cordula (nee Malbunka) were the first generation Ebatarinja painters, followed by Walter’s nephew Arnulf Ebatarinja. The career of Walter and Cordula’s talented son Joshua ended tragically with his death aged thirty-three. Desmond Ebatarinja, a younger brother of Joshua is still active as a painter.

Eric Ebatarinja, (born 1918) who produced a striking painting in the late 1940s did not pursue a career. The author thinks Eric was probably a younger brother of Walter. Eric’s brother was Benjamin Landara (born Ebatarinja), who married Albert and Rubina’s daughter Maisie Namatjira. Benjamin was the 17th founder to start painting seriously and had a career as a painter. Benjamin, guided by Albert, received special attention as his son-in-law. He did not use the Ebatarinja surname. He is discussed separately under his name Benjamin Landara. Walter’s nephew Arnulf Ebatarinja developed an outstanding all over style of patterning.

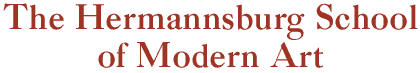

Finke Gully

Walter Ebatarinja

• • •

est. 1945

Watercolour on paper

24 x 32 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-WEb-11

This cautious but delicate and naïve early painting is elegant and rhythmic and contains many characteristics of the artist’s great future works, namely: minimally indicated foliage; understated rhythmic parallels; use of unpainted paper as part of the colour and texture system; a shimmering appearance from sketch point onwards; and pink. The composition is paler than Albert’s work.

There are no Edwin-influenced broad colour fields or under washes. The most luminous areas are in the lemon based foliage and lemon on the side of the tree trunks.

Walter’s pencil outlines of the top of the hill and tree trunks plus the stepped hill right mid-ground are further developed in later paintings. Parallels on hill, blobs and delicate blob foliage were all refined during his career. There is almost no colour on the sky, which is of the palest blue. There are cautious cerulean blue marks on hill. The pale pink blob marks on the hill are a little more relaxed. Walter employed unpainted paper on mid-ground and right of tree trunks as comfortably as if he was using the surface sand in a ground ceremonial design.

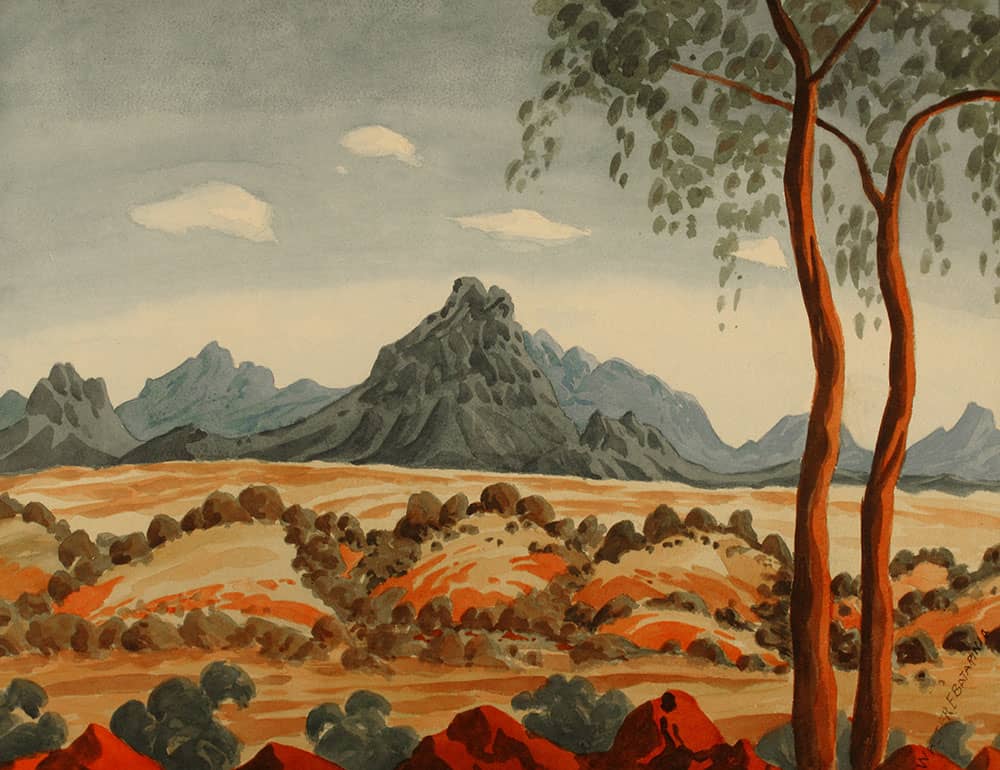

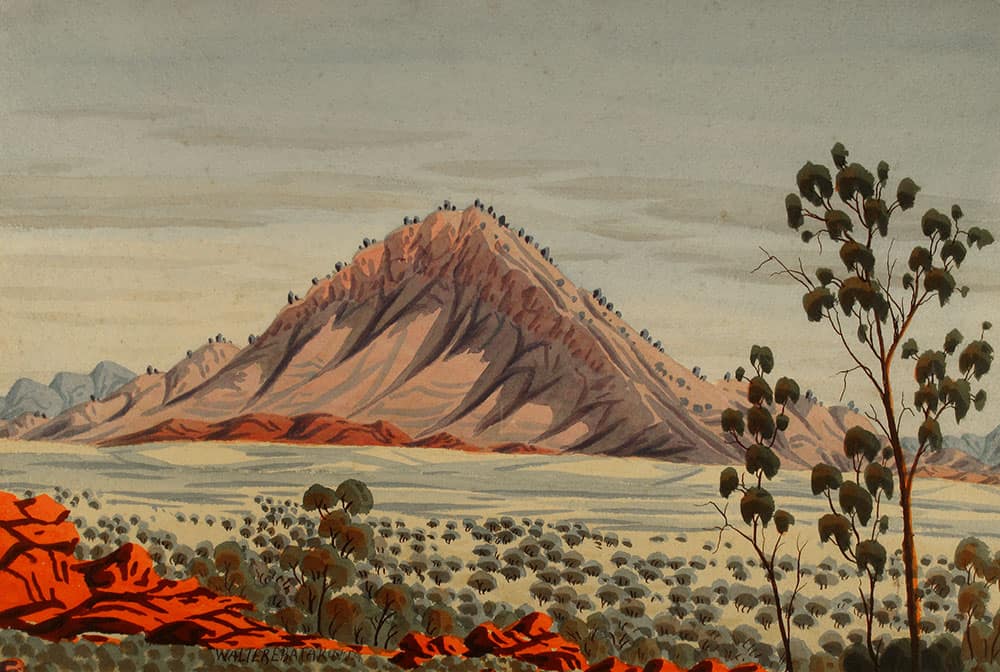

MacDonnell Ranges near Alice Springs

Walter Ebatarinja

• • •

est. 1945

Watercolour on paper

37.5 x 25.7 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-WEb-22

This very early delicate painting is pale like Finke Gully. It is well composed and resolved and shows more experience. The blob infill marks are a decorative part of the design. There is a sparse use of fine pencil outlining on hills and a few small trees are marked in and then ignored as the painting progressed.

The trunk of the large tree on the right is not outlined in pencil. It is outlined in fine delicate colour as if by pen or very fine brush and applied with a very steady hand. The artist was sensitive to the finely textured felt surface of the cotton rag-mat (pressed) paper. The white of the tree trunk is unpainted unlike the sky and foreground. In later paintings, Walter used the felt texture of the paper more confidently, for instance by leaving a white riverbed in Palm Valley as unpainted grainy paper.

The sky and areas of foreground are in palest flat washes of blue (sky) and yellow ochre (foreground). The artist carefully created a pale and delicate painting. There is no geometric interest in this painting in pencil, as there was on his first. However, large areas of palest wash now show appreciation of Edwin’s painterly approach. The painting is sharpened up with more intense red ochre dots and painted line work on the big tree and foreground rocks. The red ochre continues with finer more skilled paintwork in the central mid-ground small tree and centre scrub branches.

By 1945 Walter started to apply more intense colour as demonstrated in Finke River Bank (1945; watercolour on paper; 39.5 x 28.5 cm. Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory; NAM-0147)

Curator and writer John Kean thinks the high distant hill is possibly Blanche’s Tower at Winparku.

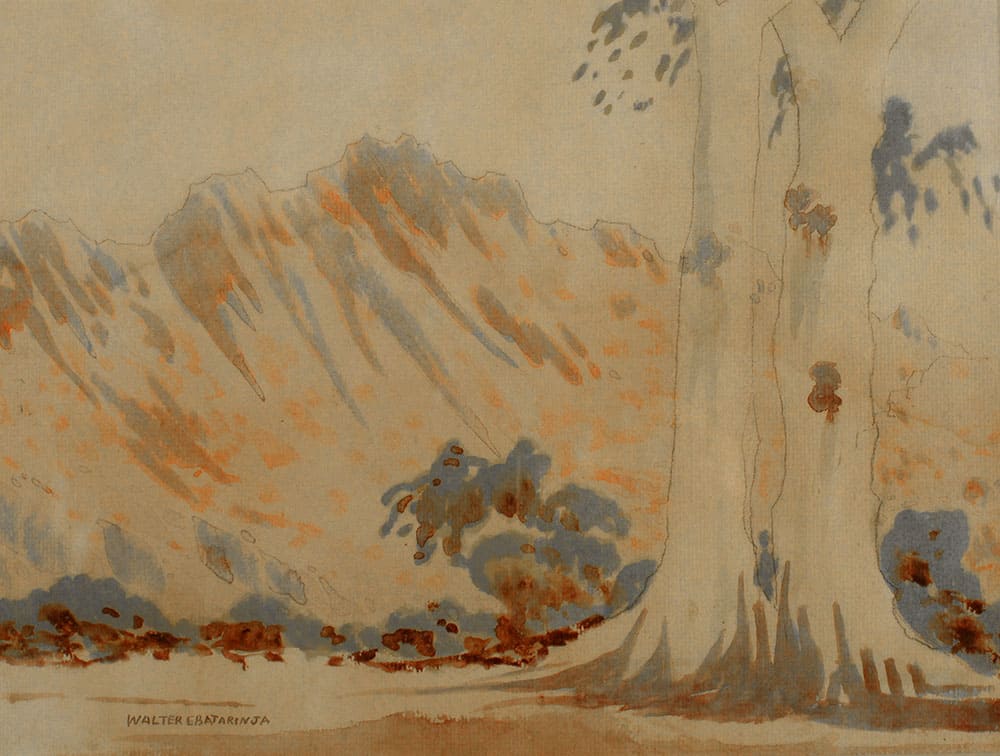

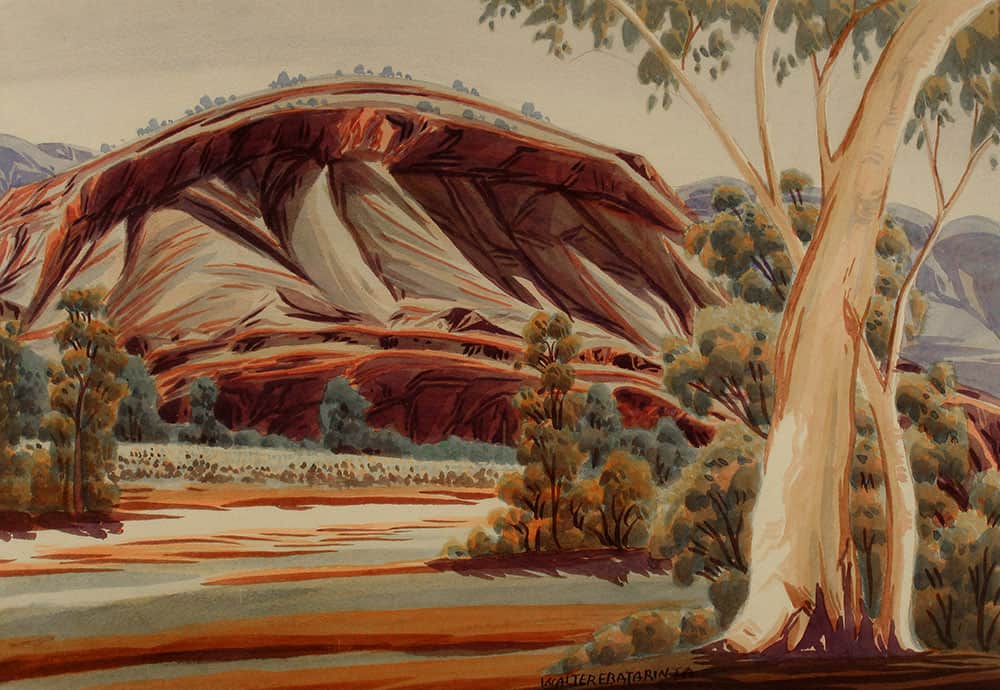

Central Australian landscape

Walter Ebatarinja

• • •

est. 1947-49

Watercolour on paper

37 x 47 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-WEb-19

This landscape is a design based on horizontal patterning for both decoration and a means of establishing distance. The distant hills inspire the patterning of the mid-ground band of small rounded hills, which are outlined in traditional blob/dot fashion. The gently curving tall trees unite the horizontal areas of the composition.

The obviously separated colour fields in Walter’s perspective were perhaps inspired by Edwin’s use of colour fields. The sky and distant hills are based on cobalt blue.

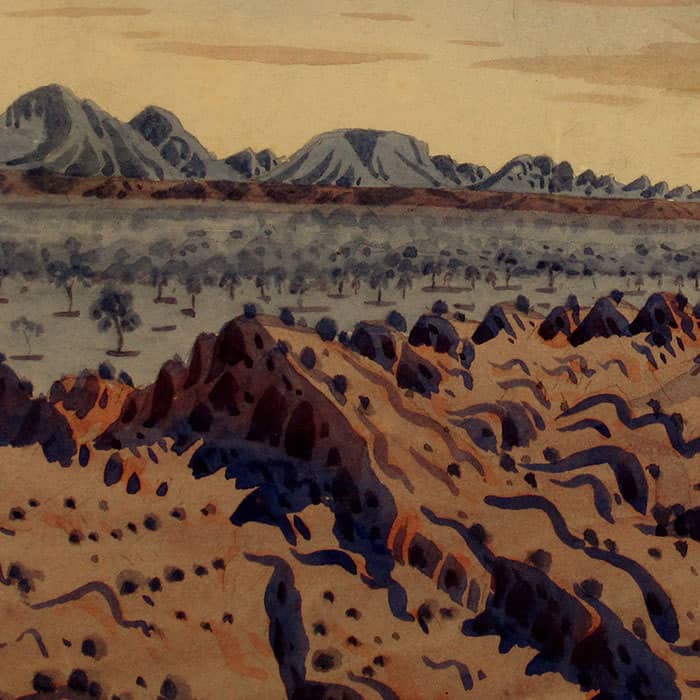

James Ranges

Walter Ebatarinja

• • •

1952

Watercolour on paper.

36.5 x 45 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-WEb-14

In this assertion of personal and tribal identity, the near half of the painting involving the foreground, is described in tjurunga type markings for the viewpoint hill. The view is toward an Albert-style distant range across a narrow plain with traditional infill then employed by Albert to suggest small trees and shadows.

The near side of the plain has Walter style trees and shadows which blend the plain to Walter’s personal space. This composition seems symbolic of how Walter saw the difference between him and Albert.

Early morning light reveals a shimmering scene in which the foreground hill has palest magenta and ultramarine blobs and loops behind an over wash of mauve. A few areas of pink were left uncovered to shimmer. Bold ultramarine loops, dots and wash areas reiterate the smaller marks. Palest blue blobs on plain behind more intense blob trees. Loops in foothills. Cobalt blue sky receding palest yellow at horizon. Hint of yellow ochre in wash. Greyed clouds. This is sunlit from low right. Foreground is ultramarine, highlighted with magenta.

On the back of the painting is an expertly drawn pencil sketch of a cut-off tree by another hand, done as if in conversation and demonstration.

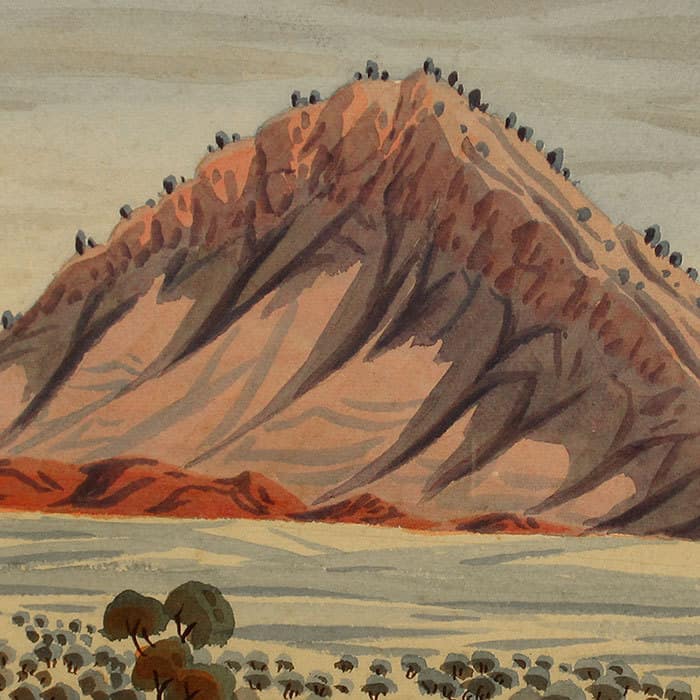

Australian Interior

Walter Ebatarinja

• • •

est. 1954-56

Watercolour on paper

38 x 56 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-WEb-05

Walter presented this version of an important totemic hill as seen on a bright but cool wet-season day. The hill stands emphatically on the plain. Delicate wavy tjurunga style marks on the side of the hill possibly refer to deeper meaning and history of the hill, perhaps as a label to ‘those in the know’.

A further delicate band of pale diamond-like patterning separates the near ground from the base of the hill, thus setting off its presence.

Viewed from a high point on the plain, the foreground rocks sparkle as if after rain. The small silhouette trees of the foreground seem like by-standers to the scene.

The sky with its delicate clouds is tied in to the design. Emphatic long parallels emphasise the shape of the magenta hill. The cream of plain is a very pale wash of yellow with yellow-green in bottom foreground strip. Foothills are nature based geometric. All of the plain is patterned. Fine black pen on trunks.

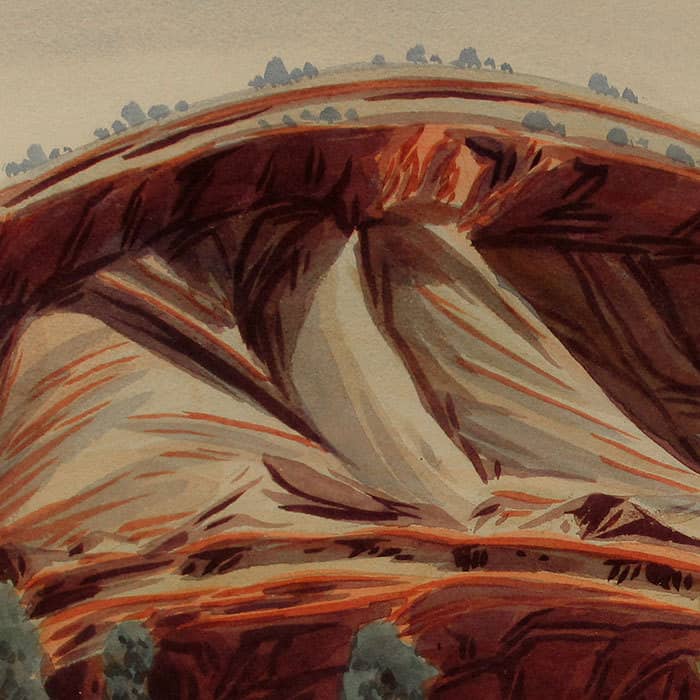

The Amphitheatre, Central Australia

Walter Ebatarinja

• • •

1962

Watercolour on paper

35.5 x 52.5 cm

Beverley Castleman Collection

BDC-WEb-09

This is an emphatic statement about the importance of the Amphitheatre in Palm Valley. Relief from visual clutter increases the impact of this image. The long smooth parallel marks on the amphitheatre cliff are like the fine marks incised on implements made well to increase their efficacy, such as on a boomerang.

Walter’s parallel markings plus fine dotting and painterly blobs and simplification drive this expressive interpretation.

The ultramarine distant hills and magenta hill are stylised. Lemon band at base of hill and lemon behind foliage increase the luminous effect. A row of blob trees, perhaps symbolically screens the base of the hill.

Walter painted for 22 years before his death in 1968. He seems to have lived in Alice Springs for periods, likely at an artists’ camp on the Todd River. Palm Valley was also a favoured area.

REFERENCES TO EXTERNAL TEXTS

[1] Rex and Bernice Battarbee, Modern Aboriginal Paintings [2] Diane Austin-Broos, Arrernte Present, Arrernte Past: Invasion, Violence, and Imagination in Indigenous Central Australia, p216 [3] Jane Hardy, J V S Megaw and M Ruth Megaw eds., The Heritage of Namatjira: The Watercolourists of Central Australia, p43